What Does Yellowing or Chlorosis Tell Us About the Health of a Plant?

Yellowing, also known as chlorosis, is a symptom commonly observed in plants in agricultural fields and gardens. Diagnosing its cause accurately is not always straightforward. Yet, just like a fever in humans is usually indicative of the body’s attempt to fight a viral or bacterial infection, chlorosis in a plant is usually suggestive of some dysfunction in the pigments that give most plant species their normal green color. But, what exactly are those pigments? What is chlorosis and what causes it? How can chlorosis be treated? This MontGuide addresses these questions and gives some examples of plant chlorosis.

Last Updated: 01/22by Oscar Perez-Hernandez, MSU Extension Plant Pathologist, and Clain Jones, MSU Extension Soil Fertility Specialist

Pigments that give plants their green color. The colors we perceive in objects around us are due to the reflection of visible light from those objects back to our eyes. Thus, the green color we typically recognize in plants is due to the reflection of green light off plant surfaces. This reflection is caused by substances called chlorophylls, which reflect light of certain wavelengths (mainly green) while absorbing others. Chlorophylls belong to a class of pigments that are abundant in leaves. They contain several chemical elements in their structure, namely, carbon, hydrogen and oxygen as well as nitrogen and magnesium. Chlorophylls are found inside compartments of plant cells called chloroplasts. Within these compartments, chlorophylls function as antenna that transmit light to other molecules in photosynthesis: the fundamental process through which plants convert solar energy into sugars. When chlorophyll molecules or chloroplasts are destroyed, no longer formed, or formed at a reduced rate, green light is no longer reflected and yellow light is reflected instead; thus, plants will appear yellow.

What is chlorosis? In botany, the term chlorosis simply means lack of chlorophyll in plant tissue; it is a technical word for yellowing, mainly of the leaves of a plant. In a plant, chlorosis can be manifested in different ways. Often, it appears as yellowing of the entire plant and sometimes as yellow islands on leaves; yet other times it shows up as yellowing between the leaf veins, which is called interveinal chlorosis.

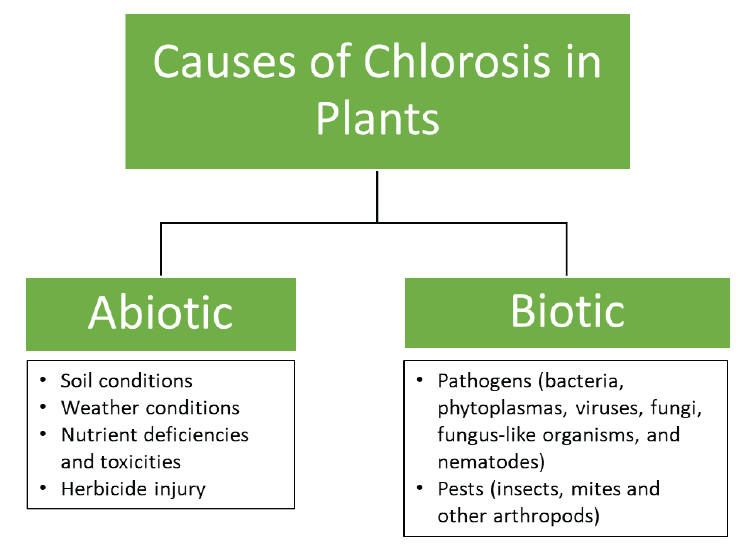

What causes chlorosis? Chlorosis in plants can have different causes. In some cases, it is part of the normal plant internal processes, for example dying of leaves or ripening of fruit. In other situations, it can be indicative of adverse factors affecting chlorophyll molecules directly, or indirectly through destruction of plant cell chloroplasts. The exact biochemical pathways of chlorosis are not well-known. The adverse factors causing chlorosis can be classified into abiotic and biotic (Figure 1).

Abiotic Causes

Physical and chemical soil conditions, rainfall, temperature, solar radiation, nutrient imbalances, mineral toxicity, and herbicide injury are abiotic factors that can lead plants to develop chlorosis.

Soil conditions. Soil conditions such as compaction and poor drainage affect root growth, and therefore, a root’s ability to absorb water and nutrients. As a result, the plant leaves will become yellow. Low soil pH (i.e. acidity) can also lead to chlorosis by making some nutrients unavailable to the roots.

Figure 1: Summary of possible causes of chlorosis in plants.

Weather conditions. Weather events such as extreme temperatures (cold or heat), excess rainfall or drought can also induce chlorosis. Extreme temperatures can cause plants to start wilting and become chlorotic. Drought conditions may also lead to chlorosis, followed by browning of the leaves and leaf loss. Such symptoms are common in seedlings that are not yet well established. Chlorosis that is induced by cold conditions is common in spring on young, actively-growing leaves. Affected leaves may remain chlorotic for the rest of the season.

Nutrient deficiencies and toxicities. Most nutrient deficiencies cause chlorosis, because most nutrients participate directly or indirectly in chlorophyll production. Nitrogen and sulfur deficiencies both cause uniform leaf yellowing; nitrogen on lower leaves first and sulfur on upper leaves first. The reason for differences in where chlorosis shows up first is due to variation in mobility of the nutrients within a plant. Some nutrients, like nitrogen, are mobile in a plant, meaning they will move from lower shaded leaves to upper sunlight-exposed leaves where photosynthesis is often higher. Deficiencies of nutrients like potassium result in yellowing mainly on leaf margins or in white spots near leaf edges, as it occurs on alfalfa. Iron and zinc deficiencies result in interveinal chlorosis. A lack of chloride in wheat can cause yellow to orange ovals on leaves. Nutrient toxicities can also result in chlorosis, but they are far less common than deficiencies. For a more complete description of nutrient deficiency and toxicity symptoms, including photos, please go to: https://store.msuextension.org/Products/Nutrient-Management-Module-09-Plant-Nutrient-Functions-and-Deficiency-and-Toxicity-Symptoms-4449-9__4449-9.aspx

Herbicide injury. Chlorosis of leaves can also be caused by herbicide injury. The pattern of symptoms depends on the involved herbicide type. Some herbicides like those containing glyphosate, paraquat and fluazifop can cause general chlorosis of plants under certain conditions; others, especially those that are taken up by the roots, can cause interveinal chlorosis. Examples of these are Atrazine, Linuron, and Metribuzin. Yet, other herbicides can cause chlorosis of the leaf veins only (Figure 2). Often, herbicide injury is associated with other symptoms such as distortion, browning, or dieback. The injury can be the result of an herbicide overdosage, herbicide tank contamination, or from herbicide drift from neighboring fields. In addition, injury can also be caused by residues of soil-applied herbicides.

Biotic causes of chlorosis

Biotic agents that can induce chlorosis in plants include pathogens causing infectious diseases, and insects, mites and other arthropods causing transient plant irritations. Plant pathogens induce infections that interfere with primary and secondary metabolism, which are related to plant growth and development and the initiation of plant defense strategies, respectively. Insects, mites and other arthropods feed on plant parts by piercing and sucking the content (juices) of plant cells. This often results in chlorotic foliage.

Figure 2: Chlorosis in potato plants caused by a foliar treatment with a tank contaminated with the herbicide Mesotrione. By Jed Colquhoun, University of Wisconsin, Bugwood.org #5554018

Plant pathogens. When a pathogen starts procuring nutrients from plant cells it interferes with functions, which can lead to chlorosis. In most cases, the chlorosis is caused by a reduction in the amount of chlorophyll per chloroplast rather than by a reduction in the chloroplast number. Less chlorophyll can be due to increased chlorophyll breakdown or reduced synthesis. Pathogens that can induce chlorotic symptoms are bacteria and bacteria-like organisms, viruses, fungi and fungal-like organisms, and nematodes.

Bacteria and bacteria-like pathogens. Several plant pathogenic bacteria induce chlorotic symptoms in their hosts. In addition, several bacteria-like organisms called phytoplasmas are known to infect plants and cause chlorosis symptoms, especially at early leaf development.

Viruses. Leaf chlorosis is a very common symptom of a viral infection. The pattern of symptoms depends on the virus or viruses causing the infection, the host plant, and the weather conditions. Most viruses cause patterns of chlorosis, such as mosaics, mottles, streaks, and ringspots, though a few viruses cause uniform yellowing of leaves. Potato Virus Y (PVY) has different variants and some of them induce yellow flecking in some potato varieties (Figure 3). Alfalfa mosaic virus induces mottling on leaves (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Yellow flecking, leaf distortion, and mosaics caused by Potato Virus Y in the potato variety Katahdin. By PVY Photo Gallery: https://potatovirus.smugmug.com/.

Figure 4: Mottling caused by Alfalfa Mosaic Virus in a potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) leaf. By Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org #5357314

Fungi and fungus-like organisms. These groups of pathogens can cause leaves of their host plants to become chlorotic. Rust fungi and powdery mildews are known to alter the chloroplasts during infection. Downy mildews can cause yellowing of all or part of the leaf. Some leaf spot diseases (e.g., rose blackspot) cause the leaves to produce ethylene, a gas that leads to rapid yellowing and loss of leaves. Diseases of the root system, for example, Phytophthora root rot, Fusarium yellows, or Verticillium wilt can also cause leaf yellowing (Figures 5 and 6). Other symptoms will also be present, such as root decay or stained vascular tissues. The infected plant usually declines, wilts, loses vigor and may eventually die.

Nematodes. Yellowing is one of the most common aboveground symptoms caused by plant parasitic nematodes, which are roundworm-like microscopic animals that wound plant roots, tubers, stems and leaves using a syringe-like structure known as a stylet. For example, the soybean cyst nematode infects roots and causes yellowing of soybean plants. The foliar nematodes in the genus Aphelenchoides penetrate plant leaves through natural openings. Once inside, they migrate and feed on plant cells, causing characteristic interveinal chlorosis (Figure 7) and necrosis of the leaf, ultimately killing it.

Figure 5: General leaf yellowing caused by Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. betae in sugar beet. By Oscar Perez-Hernandez

Figure 6: Yellowing in a chickpea plant caused by Fusarium root rot. By Oscar Perez-Hernandez

Insects, mites and other arthropods. Pests that attack aboveground plant parts such as insects with piercing and sucking mouthparts feeding on leaves, can cause injury that is often manifested as chlorosis. Aphids and whiteflies are examples of insects that use their stylets to extract the content of cells and tissues. Other types of insects such as weevils and maggots can feed on plant roots, thereby affecting the ability of root systems to absorb water and nutrients. Mites and other arthropods can also induce chlorosis of plant organs on which they feed. The pine eriophyid mite (Triseticus sp.) causes yellowing and distortion of needles of pine trees. Other mite species, such as the two-spotted spider mite and the southern red spider mite cause chlorosis of leaves on which they feed (Figure 8).

Figure 7: Chlorosis in leaf of Hosta sp. infected with foliar nematode Aphelenchoides sp. By Jonathan D. Eisenback, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Bugwood.org #5440465

Figure 8: Chlorosis caused by the southern red spider mite in an Andromeda plant. By Steven K. Rettke, Rutgers Cooperative Extension.

Diagnosis of Chlorosis

The first step before a treatment should be implemented is to diagnose the cause. Familiarize yourself with what is normal for the plant or crop variety being grown. Some plant varieties could show yellowing patterns that are normal to the variety. Here are the basic steps to help diagnose the problem:

1. Observe the symptoms. Observe the pattern of symptoms in individual plants and leaves. Determine if the symptoms are occurring in lower leaves or upper leaves, and if the chlorosis is interveinal or on the entire leaf area. Observe if neighboring plants show the same type of symptoms. If possible, dig up some plants and examine the roots to determine if they look healthy and normal or if they show any signs of damage or disease.

2. Look for other signs. Look for other signs associated with the symptoms, for example, fungal growth (mycelium, fruiting bodies), insect feces, or insect themselves. This could help pinpoint if the problem is a disease or a pest.

3. Consider the soil and weather conditions. Is the soil too dry? Has it rained a lot lately? Has it been too hot or has there been a period of drought? If so, did the problem start after a drought period? Here, it is important to monitor the plants to find out if the problem is temporary or persistent. Extreme changes in soil and weather conditions may induce temporary yellowing of leaves (the symptom may go away as conditions normalize). If the chlorosis persists, then the problem needs attention. Other problems, such as soil compaction or low pH could be the cause of plant yellowing. Some plant species do not grow well in acidic or alkaline soils and will develop nutrient deficiencies of certain elements under such conditions. In this situation, one remedy is to adjust the soil pH. In other cases, a foliar application of the nutrient, for example, iron, could correct leaf chlorosis temporarily.

4. Examine the pattern of symptomatic plants in the field or area. Examine symptomatic plants in the field or area where the plants are growing. Are they individual or in patches? Are the symptoms present in most of the field or only in certain areas of the field? Patches of symptomatic plants could be indicative of a biotic cause.

5. Consider field history and management practices to date. Did the field or garden receive fertilizer based on soil tests? If so, nutrient deficiencies are less likely. Were herbicides applied; when and what was applied? Could they have caused the issue? Could herbicides have drifted from a neighboring area? Have the same or similar symptoms been observed in the past in this field or garden?

6. Consult your local Extension Agent for help in identifying the cause. Your local Extension Agent will provide ideas for treatment if they can pinpoint the cause.

Once the cause has been determined, then treatment can be initiated (treatment will depend on the cause of the problem). We recommend following an integrated management approach. Some chlorosis issues are easy to fix, like applying a nutrient that is deficient. Others, such as those caused by drought or herbicide injury, are nearly impossible to correct. If the cause is ‘abiotic,’ further testing for nutrient deficiencies or toxicities at an independent lab might be needed. https://landresources.montana.edu/soilfertility/html/SoilTestLabs.html contains a list of labs that samples could be sent to for nutrient analysis.

Summary

Yellowing or chlorosis in a plant more often than not is indicative that something is wrong with the chlorophyll or the chloroplasts, both of which take part in photosynthesis. The problem could be caused by biotic and abiotic factors. Keep this in mind before assuming that the problem is due to lack of a nutrient or caused by a disease. In the field or garden, observe the symptoms carefully in single plants and groups of plants. Look for other signs (fungal growth, insect presence, etc.), consider the soil and weather conditions, and management practices to date.

Sources

Berger, S., Sinha, A. K., and Roitsch, T. 2007. Plant physiology meets phytopathology: plant primary metabolism and plant–pathogen interactions, Journal of Experimental Botany. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erm298

Lu, Y., and Yao, J. 2018. Chloroplasts at the crossroad of photosynthesis, pathogen infection and plant defense. International journal of molecular sciences: 19: 3900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19123900

Missouri Botanical Garden. Iron Chlorosis (missouribotanicalgarden.org)

Rettke, S. K. 2013. Cool Season Mites Wax as the Warm Season Mites Wane — Plant & Pest Advisory (rutgers. edu).

University of Illinois Extension. Chlorosis | Focus on Plant Problems | U of I Extension (illinois.edu)

What causes a fever? 2005. The Scientific American, a Division of Springer Nature America, Inc. (Nov 21, 2005). Copyright © 2005, Scientific American, Inc.