Herbicides: Understanding What They Are and How They Work

Herbicides are a class of pesticides used to kill or suppress weeds. This MontGuide introduces key concepts necessary for managing weeds and using herbicides safely and effectively.

Last Updated: 07/21by Noelle Orloff, Associate MSU Extension Specialist; Jane Mangold, MSU Extension Invasive Plant Specialist; Tim Seipel, MSU Extension Cropland Weed Specialist; and Cecil Tharp, MSU Extension Pesticide Education Specialist

Introduction to Weed Management

A weed is a plant growing somewhere humans do not want it. Any plant can be considered a weed if it becomes a hazard or nuisance, injures animals, reduces crop or forage yield, or infests rangelands, pastures, lawns, or gardens.

There are different types of weeds based on the risk they pose to agricultural production or natural resources. Some weeds are a minor nuisance, like dandelions growing in a lawn. Other weeds have larger impacts such as reducing crop yield or impacting biodiversity. There are even noxious weeds designated by the state or county because they negatively impact agriculture, forestry, livestock, wildlife, or other beneficial uses, or may harm native plant communities. Landowners are legally responsible for controlling noxious weeds on their land [1].

Many people choose to use herbicides, which are a type of pesticide, to control weeds. Pesticides include a broad range of substances that are applied to unwanted organisms that include insects (i.e., insecticides), fungi (i.e., fungicides), and many others.

Herbicides are chemicals used to kill plants or suppress their growth by interfering with normal biological processes.

Figure 1. Herbicides are an important part of integrated weed management. Photo credit Jesse Scott, Carter County Weed District.

Integrated weed management (IWM) uses multiple strategies to manage weeds in a way that is economically and environmentally sound, and herbicides are one part of this framework (Figure 1). In an integrated weed management program, herbicides should be used with cultural, mechanical, and biological methods to keep weed populations at a tolerable level while protecting water quality and other natural resources [2]. For example, an IWM approach to control some noxious weeds in rangelands might include sheep grazing to target the weed, in addition to strategically-timed herbicide applications.

Weed Biology

Certain characteristics of plants are important to understand when considering herbicide use because they influence the effectiveness of a herbicide. Two important characteristics are how long a plant lives (i.e., annual, biennial, perennial) and whether it is a grass-like or broadleaf plant (i.e., monocot or dicot).

Plant life cycles Plant species are classified as annuals, biennials, or perennials. Effectiveness of weed management often depends on knowing the weed’s life cycle and targeting weeds during certain growth stages.

- Annual plants complete a life cycle in less than 12 months and grow from seed each year. Management requires stopping seed production, exhausting the seed bank in the soil, and limiting soil disturbance.

- Biennial plants complete a life cycle within two years. In the first year, the plant forms basal leaves (rosette) and a tap root. In the second year, the plant flowers, produces seed, and dies. Like annual plants, biennial plants reproduce only by seed, so control must occur before seeds are produced.

- Perennial plants live more than two years, and some may live many years, re-sprouting from vegetative plant parts (e.g. roots, rhizomes, stolons, tubers). Because of persistent, re-sprouting vegetative parts, some perennial plants can be very difficult to control. Most reproduce by seed, and many spread vegetatively as well.

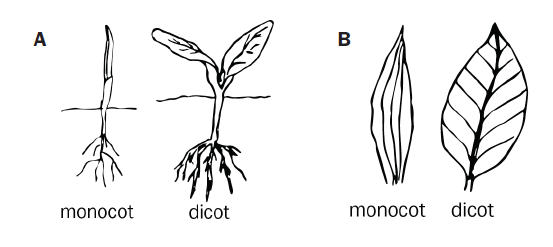

Monocots (grasses) and Dicots (broadleaves) Plants are divided into two major groups: grasses or grass-like plants (monocots) and herb-like plants or broadleaves (dicots) (Figure 2). It is important to know the difference between these two groups to choose an effective herbicide. Some herbicides work on all types of plants, but many herbicides control either grasses or broadleaves (see “Herbicide Selectivity,” below).

- Monocots (mostly grasses) have one seed leaf when they emerge. Leaves are narrow and upright. Leaf veins are parallel to leaf margins. In addition to grasses, monocots include sedges, rushes, lilies, and irises.

- Dicots (broadleaf plants) have two seed leaves when they emerge. Leaves are generally broad with net-like veins. Plants may be herbaceous, which means they have no woody tissue and die back to the ground each year, or they may be woody like shrubs and trees.

Figure 2. Illustrations of a) seedlings and b) mature leaves for monocots (grasses) and dicots (broadleaf plants). Drawings by Hilary Parkinson.

What’s in the Bottle? Ingredients and Formulations

Herbicide products (Figure 3) have two categories of ingredients, active and inert. An active ingredient is the chemical that disrupts the biological process of the weed and kills or suppresses it. Active ingredients are listed on the label. Inert ingredients make the product easy and convenient to apply by providing benefits like reducing drift or increasing absorption into plant tissue. Even though inert ingredients are not usually specified, examples include surfactants, solvents, fragrances, carriers, and dyes. Together, active and inert ingredients constitute an herbicide formulation.

There are different types of herbicide formulations. Formulations can be categorized as either liquid or dry. Liquid formulations are often mixed with water and applied as a dilute spray, while dry formulations may be either mixed with water and applied as a spray or applied in the dry form. Some examples of liquid formulations use acronyms such as L for liquid, F for flowable or EC for emulsified concentrate, while some examples of dry formulations use acronyms such as DF for dry flowable, WP for wettable powder, G for granular or D for dust. Knowledge of formulations and reading the product label helps applicators understand safety hazards, handling considerations, and the type of equipment needed to apply the product safely and effectively [3][4]].

Figure 3. Herbicide products contain both active ingredients and inert ingredients (Photo credit Jane Mangold).

When to Apply Herbicides: Timing and Thresholds

For best results, herbicides need to be applied at the right time. Often, annual weeds need to be sprayed when they are small. Sometimes, application timing is prescribed according to the maturity of weeds. Early growth stages are commonly more susceptible to herbicides than late growth stages when plants develop a thick, waxy cuticle or enter dormancy to reduce water loss under hot conditions.

An often-overlooked tenet of IWM is the concept of thresholds. A threshold is the point where control action should be taken to reduce economic or environmental loss. In other words, it is the point where the cost of controlling weeds is less than the cost of not controlling weeds, whether the cost is measured economically (e.g. reduced crop yield) or ecologically (e.g. reduced native plant diversity). In some settings, a few or even many weeds can be tolerated. But, with certain damaging noxious weeds, a zero-tolerance approach is needed. Properly identify and monitor weeds to determine when and if control is necessary.

Herbicide Activity and Selectivity

To use herbicides successfully, you must understand how herbicides:

- enter and move in plants,

- kill or control plants, and

- can be used to kill only the target weeds

HERBICIDE MOVEMENT—CONTACT VERSUS SYSTEMIC HERBICIDES

Contact herbicides are applied to plant foliage and impact only those parts of the plant they contact directly. They do not move throughout a plant after they are absorbed. They rupture cell membranes and cause rapid cell death. Activity is often very quick with visible damage occurring in a few hours under ideal conditions. Good coverage is essential to achieving control with contact herbicides.

Contact herbicides are most often used when controlling annual weeds; they kill only the shoots of perennial weeds, leaving the roots to re-sprout. Repeated applications of contact herbicides to perennial weeds may deplete energy reserves in underground plant parts, eventually causing death. Contact herbicides are commonly used in croplands to control emerged weeds either before planting a crop or after planting but before crop emergence, or as crop harvest aids (desiccants).

Systemic herbicides are absorbed through foliage, shoots, or roots, and move within the plant. These herbicides move within a plant’s water or sugar transport system, often to roots or growing points. Good control requires applying the herbicide to actively growing plants which are transporting sugars and water, thus moving the herbicide throughout the plant. For example, if the plant is stressed from heat or drought and not growing actively, poor control may result.

To choose an effective herbicide for a weed, consider the weed’s life cycle. For example, movement of an herbicide into roots is important when controlling perennial weeds and biennial weeds; movement into roots is less important for annuals, but still helpful for providing season-long control. Systemic herbicides are good choices for perennial and annual weeds.

Herbicide Selectivity

A plant can be either susceptible (injured or killed) or tolerant (survives without injury) to a given herbicide.

Selective herbicides control certain weeds while doing little or no damage to other types of plants. For example, many herbicides selectively control broadleaf plants without injuring grasses. Other herbicides selectively kill grasses and not broadleaf plants. A common herbicide that is selective for broadleaf plants is 2,4-D. Conversely, a common herbicide that is selective for grasses is sethoxydim.

Nonselective herbicides kill or suppress growth of almost all types of plants. Examples of nonselective herbicide active ingredients are glyphosate and paraquat.

Selectivity can be affected by many factors including the amount of herbicide applied, how and when it is applied, and under what environmental conditions. Selectivity may be lost through applicator error or by applying herbicides to stressed plants or plants at the wrong growth stage. Consult the product label for information on selectivity, use rate, application timing and other information to maximize weed control and limit injury to other plants.

SOIL-RESIDUAL HERBICIDES

Soil-residual herbicides persist in the soil and remain active over a period of time. Depending on soil type, rate of application, and herbicide properties, soil residual herbicides can control weeds for several weeks to several years [5].

In croplands, applicators should consider whether short- or long-term residual activity is desired. Herbicides that persist for months to years may offer long-term control of difficult to manage weeds, however, future crops could be injured. In rangeland and pastures, long-term residual activity is often desired. This allows for weed control throughout a growing season and into subsequent years. However, if range or pasture seeding is planned, residual herbicides can injure future plantings of sensitive species. Information about expected residual periods is usually available on the product label.

Herbicide Classification: Mode of Action and Site of Action

Mode of action (MOA) classifies herbicides based on the general way they kill plants. There are eight generally accepted herbicide MOAs. For example, herbicides in the amino acid synthesis inhibitor MOA stop plants from producing specific amino acids that are needed for plant growth. As another example, herbicides in the photosynthesis inhibitor MOA disrupt various processes in photosynthesis leading to different types of reactions that are lethal to plants.

Within each MOA there may be multiple sites of action (SOA) (Table 1). An herbicide SOA is the specific biochemical pathway an herbicide acts upon in a plant. For example, there are several SOAs within the amino acid synthesis inhibitor MOA that each target the function of a specific enzyme. One reason SOA is important to understand is that the SOA is the most critical factor to consider when selecting herbicides to manage herbicide-resistant weeds (see “Herbicide Resistance” below). The SOA group number designation is often included on the herbicide product label. A comprehensive list of herbicide SOA groups can be looked up by number at the Herbicide Resistance Action Committee website.

Herbicide Resistance

Herbicide resistance is the inherited ability of a weed to survive and reproduce after treatment with a dose of herbicide that would normally kill it. Herbicide resistance causes serious issues for farmers such as reduced ability to control weeds and increased herbicide and equipment costs. It occurs due to repeated use of the same herbicide or type of herbicide (i.e., MOA or SOA). Worldwide, herbicide resistance is a serious issue, and in Montana herbicide resistance is a growing problem.

Table 1. Examples of herbicide products with their active ingredients, sites of action (SOA), group numbers, and modes of action (MOA).

| Herbicide Product Examples | Active Ingredient | Site of Action | Group Number | Mode of Action |

|

Spartan 4F

Gramoxone SL |

Sulfentrazone

Paraquat |

PPO Inhibitor

Inhibition of Photosystem 1 |

14

22 |

Cell membrane disrupters |

|

Ally XP

Roundup Pro |

Metsulfuron methyl

Glyphosate |

ALS Inhibitor

EPSP Synthase Inhibitor |

2

9 |

Amino Acid Synthesis Inhibitor |

To avoid herbicide resistance, it is important to avoid using herbicides in the same SOA group number in the same field in consecutive applications. Furthermore, using reduced herbicide rates often increases the risk of herbicide resistance; use the recommended rate on the product label. Another important strategy is to use IWM techniques and avoid over-reliance on herbicides, so that weeds do not have a chance to evolve herbicide resistance [6].

Using Herbicides Safely

If used improperly, herbicides can be harmful to humans and the environment. Read the product label to find the signal word that relates to a product’s acute toxicity while watching for chronic toxicity statements. The signal words in order of increasing acute toxicity are Caution, Warning, and Danger Poison. Follow instructions regarding use of all required personal protective equipment (PPE) needed to mix, load, and apply the product safely. Carefully read regulations on the product label that are intended to protect the environment. For example, the label might include regulations about wind speed at application, proximity to sensitive plants, and minimum distance between an herbicide application site and surface water. It is also important to use herbicides at recommended rates with calibrated equipment, so the correct amount of herbicide is applied [7][8][9][10].

Summary

Applicators should be knowledgeable about key concepts of herbicides to use them effectively and safely. For more information about the topics covered in this publication, see the list of references below. For advice or recommendations for weed management and herbicide use, contact the local Extension office or weed district.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ben Hauptman; Clair Keene, PhD; and Theresa Schrum for reviewing this publication.

References Cited

[1] Goodwin, K., J. Mangold, and C. Tharp. 2019. Herbicides and Noxious Weeds: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions. EB0214.

[2] Tharp, C. 2020. Pest Management Using Integrated Strategies. MT202009AG.

[3] 2014. National Pesticide Applicator Core Manual. National Association of State Departments of Agriculture Research Foundation.

[4] Tharp, C. and A. Bowser. 2019. Pesticide Labels. MT199720AG.

[5] Menalled, F. and W. Dyer. 2010. Getting the Most from Soil-Applied Herbicides. MT200405AG.

[6] Menalled, F and W. Dyer. 2011. Preventing and Managing Herbicide-Resistant Weeds in Montana. MT200506AG.

[7] Tharp & Schleirer. 2019. Assessing Pesticide Toxicity. MT200810AG.

[8] Petroff, R. 2017. Safe Handling of Pesticides - Mixing. MT200109AG.

[9] Tharp, C. 2017. Calibrating Pesticide Application Equipment. MT200914AG.

[10] Tharp, C. 2017. Pesticides and the Environment. MT201012AG.