Backyard Guide to Codling Moth Management

It has been said the only thing worse than finding a worm in an apple…is finding half of a worm. This MontGuide describes that “worm” (which is likely the caterpillar (larva) of the codling moth (CM), a major pest of apple, pear, quince, and walnut), its life cycle, and how to monitor and manage it.

Last Updated: 04/21by Rebecca Richter, MS, Western Agricultural Research Center (WARC) Research Assistant and Content Strategist; Rachel Leisso, PhD, WARC Assistant Professor-Horticulture; Katrina Mendrey, MS, Apple Program Coordinator; Zach Miller, PhD, WARC Superintendent and Assistant Professor-Horticulture

Codling moth (CM) is a major pest of apple, pear, quince, and walnut. Keys to safe and effective CM management include:

- Understanding the pest life cycle

- Monitoring for the pest

- Timing control methods precisely to target specific life stages

- Choosing and combining appropriate control methods

- Beginning control early in spring and continuing throughout the season

- Prioritizing least-toxic control methods

Life Cycle

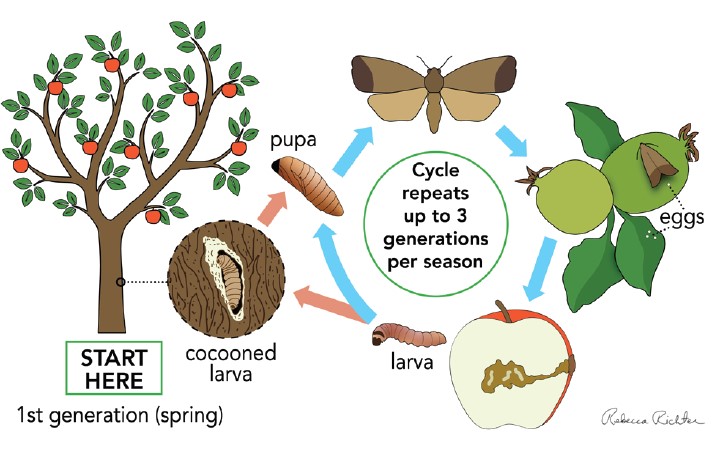

As with all insects, the CM life cycle is dependent on temperatures, which means its rate of development varies throughout the season and from year-to-year. In Montana, CM can produce up to three generations per season (spring through mid-September). Understanding its life cycle is important for accurately timing controls that target specific life stages.

The first generation of CM emerges from pupae in spring as half-inch long winged adults that are grayish-brown with a copper-colored band at the wing tips. Females lay up to 70 tiny eggs on immature fruits or nearby leaves. Eggs hatch into one-quarter-inch to one-half-inch long larvae with cream- to pink-colored bodies and black or brown heads. Larvae burrow into developing fruit to feed on the seeds. Three to four weeks later, the half-inch to three-quarter-inch long mature larvae emerge from fruit to seek shelter in protected areas such as in cracks or under loose bark on the tree trunk or in debris on the ground. There, they either pupate and transform into the next generation of winged adults or spin cocoons for overwintering. Infestation and development stop either with lowering temperatures or reduced daylength in mid-September.

Winged adult CM on apple leaf. BY GYORGY CSOKA, HUNGARY FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE, BUGWOOD.ORG #5371103

Codling moth life cycle in Montana.

Monitoring

Observing CM activity will help inform when to begin taking action and whether to scale efforts up or down and/or alter management strategy. Inspect tree fruit regularly for larval entry/exit holes (strikes or stings) and insect poop (frass) and note changes in numbers of larvae in trunk bands (below). Consider monitoring winged adult activity with an orange delta-style CM pheromone trap, available through online horticultural suppliers (see Timing Controls).

Larva and frass on cut apple. BY WARD UPHAM, KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG #5527808

Larval entry/exit holes and piles of insect poop (frass) on fruit surface. BY WHITNEY CRANSHAW, COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY, BUGWOOD.ORG #5506398

Management

It cannot be stressed enough that CM controls must be applied at the right time to affect the targeted life stage, otherwise the efforts will have little impact, may harm other wildlife, and time and products will be wasted. Keep in mind that any single method is unlikely to succeed on its own (aside from fruit bagging), so choose a combination of methods to implement throughout the CM season. Also recognize that CM is here to stay, and its management will always a part of raising crops susceptible to infestation. This guide provides only the basics of CM management for backyard apple and pear growers. For more detailed information, see Extension Bulletin 0234, Codling Moth Management in Commercial Apple and Pear Orchards.

COMMUNITY CONSIDERATIONS

Winged CM can fly a half-mile or more, so if there are unmanaged trees nearby, it will be challenging to stay ahead of orchard infestations. Consider launching a neighborhood-scale effort by organizing home orchardists to share information, pesticides or other products, and equipment. Form a volunteer group to help others with orchard sanitation (below), fruit harvest, and management or removal of abandoned trees.

CULTURAL AND PREVENTIVE EFFORTS (NO-SPRAY OPTIONS)

Leaving codling moth-infested fruit and debris in the orchard will lead to increased infestations. Keep leaves raked, remove fallen twigs, pick up dropped fruit, and remove infested fruit from trees throughout the season. Appropriate disposal options for this waste include mowing/shredding, burning, bagging for trash removal, deeply burying, or immersing in soapy water for two to three weeks.

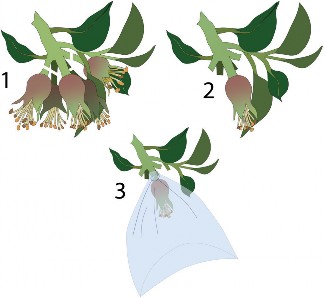

A combination of fruit thinning and bagging can reduce disease and insect damage and improve apple quality. Fruit is bagged immediately after petal fall to prevent CM from laying eggs on the fruit. Although labor intensive, this method eliminates the need for a season-long spray program. Thin fruit by removing all but one fruit per cluster with a sharp pair of scissors or pruners. Finding the right type of bag is key. Montana researchers were able to reduce CM infestations with plastic or nylon bags. However, some fruits still became infested, and the bags caused other problems, leading researchers to suggest either using a different bag type (such as the double-layered Japanese apple bags sold online) or spraying the trees with horticultural oil once and allowing to dry prior to bagging. The latter method would eliminate any eggs that may have already been laid on the fruit. Apply bags in dry conditions, as trapping moisture inside can lead to other pest and disease issues. Note that some fruit may be lost after bagging due to natural fruit drop.

Fruit thinning and bagging.

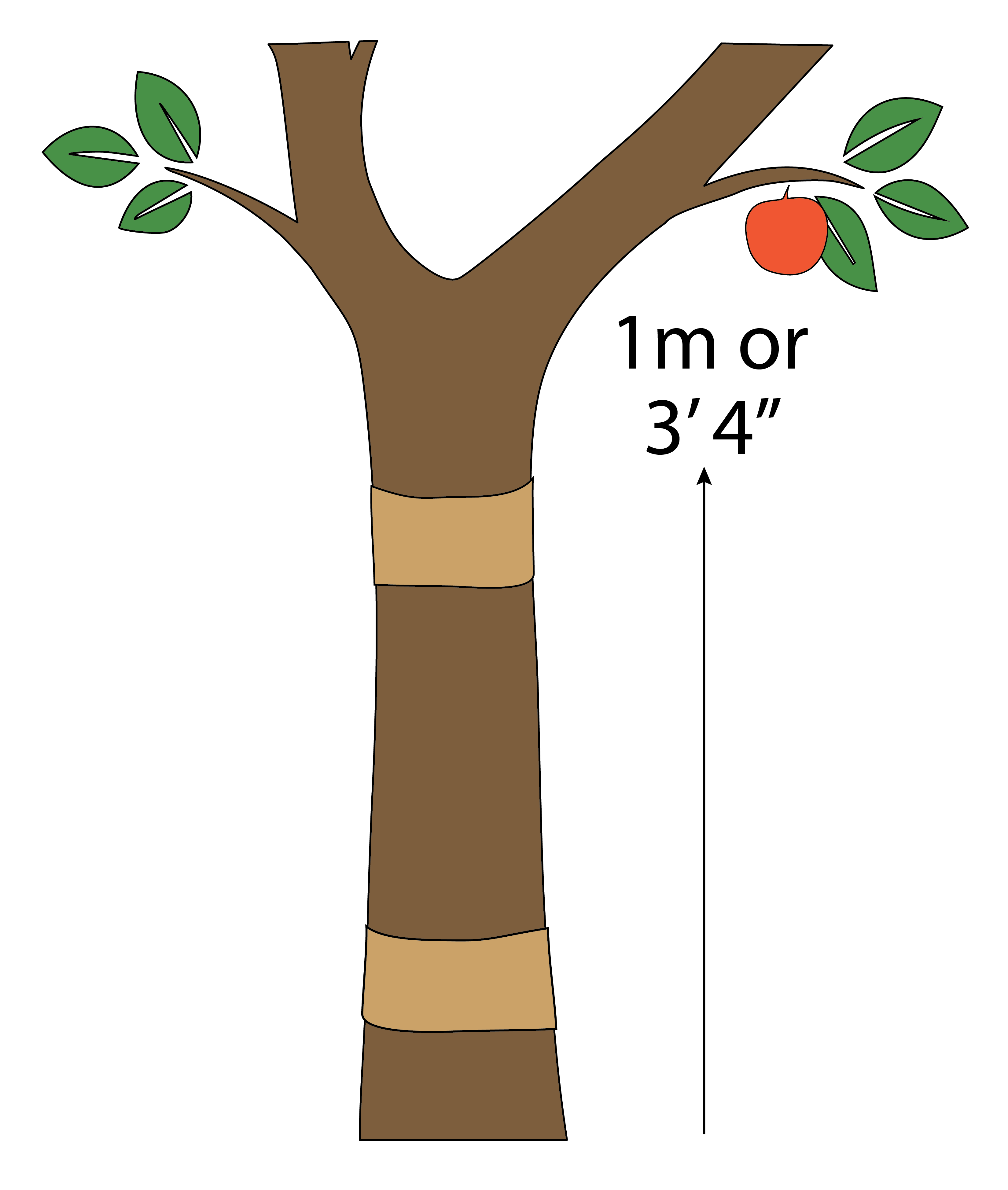

Trunk banding creates shelter on the host tree trunks for cocooning and pupating larvae that can be monitored and destroyed. Banding captures only a small portion of the population and only after CM have infested the fruit, so it should be used in combination with other control methods. First, scrape off any loose bark that is on the tree trunks, being careful not to scrape too deeply and damage the cambium layer (the green area just under the bark). Fashion bands of corrugated cardboard or cloth, four to six inches wide, and secure one or more bands tightly around trunks in the zone shown, with corrugations or textured side against the trunk. Place the first set by mid-June. Remove, destroy (dispose of as for orchard waste, above), and replace bands in early- to mid-July. Remove and destroy the second set in October.

Trunk banding.

BIOLOGICAL CONTROLS

Natural CM predators (biological controls) can be encouraged by minimizing pesticides and making the orchard attractive to insect-eaters such as bats, birds, and spiders. Several CM biological controls are commercially available, and the entomopathogenic nematode (EPN)–a tiny, soil-dwelling roundworm–may have potential for backyard growers. The nematodes are applied after harvest to target cocooned larvae on trunks and on the ground beneath trees. The most effective EPN species for cooler climates is Steinernema feltiae, which can be obtained from various online retailers.

Apply nematodes in mid-to-late September when daytime temperatures are still above 50°, humidity is high (ideally above 85%), and wind is minimal. Make two applications, one week apart. Mix EPN formulations with water according to product instructions and apply with a lance applicator or watering can onto the ground near the base of each tree. If trees have rough, loose, or cracked bark, spray trunks and lower branch junctions as well, to a height of three feet above ground. If humidity is low, spray the treatment area with water prior to EPN application and keep the area moist (but not saturated) for at least 24 hours afterwards.

SPRAY CONTROLS

Overuse of chemical sprays has caused pesticide resistance, devastation of other wildlife, harm to human health, and pollution of water and soils. It is recommended to use them only as a last resort and in combination with cultural controls described above. Codling moth sprays that target either eggs (horticultural oils) or larvae (insecticides) can be purchased from horticultural suppliers online or at a local hardware store or plant nursery. Organic and conventional horticultural oils contain either mineral oil or neem oil, which are relatively nontoxic to humans and other wildlife. Many insecticides (even organic ones) are toxic to bees and other animals, so use with caution and only after petal fall (when apple or pear flower petals have fallen to the ground). Choose insecticides that target caterpillars.

Apply sprays during calm weather towards evening or on cloudy days and when no rain is predicted for at least 24 hours. Read and follow guidelines on the product label and safety datasheet, and wear protective gear as directed. Adequate spray coverage of all branches, leaves, and fruit is essential, so consider using a hose-end applicator or hiring a fruit tree care service for spraying trees taller than 10 feet.

Table 1. Some common backyard CM insecticides

Active Ingredient(s) |

Effectiveness |

Spray interval (days) | PHI (days) |

| Organic | |||

| Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) | F | 5-7 | 0 |

| Neem oil | F | 7-10 | 0 |

| Pyrethrin | G | 3-5 | 0 |

| Spinosad | G | 7-10 | 7 |

| Conventional | |||

| Esfenvalerate | E | 14-17 | 21 |

| Gamma-cyhalothrin | G-E | 14-17 | 21 |

| Lambda-cyhalothrin, Pyraclostrobin, Boscalid | G-E | 14-17 | 21 |

| Malathion | G | 5-7 | 7 |

| Zeta-cypermethrin | G-E | 14-17 | 14 |

SPRAY REGIMENS

Try one of the spray regimens below and combine with cultural controls to minimize insecticidal applications and increase their effectiveness. Use degree-day timing (below) for greater accuracy.

Oil only (good organic option): Begin applications of horticultural oil starting just before budbreak and reapply every 7-10 days as long as significant CM flight is occurring. Oil should only be applied once in second and third generations, just before egg hatch.

Table 2. USPest and TRAPs models CM degree-days and suggested treatment timing. Use USPest model “codling moth no biofix (Jones et al 2008)” or TRAPs model “Codling moth - Fixed Biofix.”

| Life Stages | Cumulative DD | Actions |

| 1st GENERATION | ||

| Moth flight begins | 175-200 | No-spray: bag fruits as soon as possible after petal fall |

|

0% egg hatch

40% moth flight

|

375 |

No-spray: place trunk bands

Organic OO*: 1st application of hort oil Conventional DFC**: Single applicationof hort oil

|

|

15% egg hatch

68% moth flight

|

525 |

Conventional DFC: if hort oil was applied at 375 DD, apply insecticide now & again in two weeks

Organic OO: 2nd application of hort oil

|

|

54% egg hatch

90% moth flight

|

675 |

Organic OO: 3rd application of hort oil |

| Eggs hatching through 1175 DD | 930 |

No-spray: remove/destroy/replace trunk bands |

| 2nd GENERATION (only treat if needed) | ||

|

0% egg hatch

11% moth flight

|

1255 |

Conventional & organic DFC: apply hort oil once

Organic OO: apply hort oil once

|

|

15% egg hatch

50% moth flight

|

1525 |

Conventional & Organic DFC: apply insecticide at intervals according to label through end of egg hatch. Check label for PHI (preharvest interval, or when it’s safe to harvest fruit after the last spray).

Organic DFC: apply insecticide three times at intervals according to label

|

| Egg hatching through 2295 DD | Temperature- dependent actions |

Biological Control: in mid-Sept., make two applications of EPNs, one week apart

No-spray: remove/destroy trunk bands in Oct.

|

| 3rd GENERATION (only treat if needed) *** | ||

| Eggs hatching | 2335 –Sept. 15 | Apply OO and DFC treatments as for 2nd gen. Check product label for PHI. |

Oil + insecticide (delayed first cover): Apply horticultural oil once after petal fall. Apply insecticide one week later and repeat at intervals stated on the label. To reduce development of resistance, alternate insecticidal products with each spray or in different seasons. First generation egg hatch begins about three weeks after full bloom, with peak egg hatch beginning about a week later, so be vigilant with control during this period.

TIMING CONTROLS

Controls need to be applied at the right time or they won’t be effective. Some environmental cues and approximate calendar dates are provided for the control methods listed above. For more information, read and follow all directions on the product labels and contact a local Extension agent for additional information and advice. Never apply chemical controls during bloom when risk of harming pollinators is high.

A more accurate method for timing controls uses timeline units of degree-days rather than calendar dates. Degree-day (DD) timelines follow the rate of codling moth development. There are two free online models–TRAPs and USPest–that calculate CM DD automatically. See instructions for selecting and using either of these models at https://agresearch.montana.edu/warc/guides/apples/CM-DD-models.html. Use the DD timing method alongside the table below for taking action on specific cumulative DD.

Codling moth populations can be monitored with a pheromone trap to more accurately pinpoint the start of each CM generation. Note that these traps are not an effective CM control measure. However, observing trap catches will give a better idea of when to begin applying horticultural oils and insecticides. Maintaining and monitoring traps throughout the season can also inform about the impact of the CM control program. For more details on using degree-days, pheromone traps, and additional CM management methods, see Extension Bulletin 0234, Codling Moth Management in Commercial Apple and Pear Orchards.

Life stages based on http://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/treefruit.wsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/opm_table6a.png

Spray timing based on http://treefruit.wsu.edu/article/how-to-effectively-manage-codling-moth/

Orange delta-style pheromone trap hanging in an apple tree.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following individuals for their feedback during the development of this guide: Helen Atthowe, Teresa Jacobs, Laurie Kerzicnik, Nathan Leisso, Sara Leisso, Patrick Mangan, Mair Murray, Jack Rowan, Dave Rudell, Darlene Schubert, and Pete Smith.

References

Bessin, R., and Hartman, J. 2019. Bagging Apples: Alternative Pest Management for Hobbyists. ENTFACT-218: Bagging Apples. University of Kentucky College of Agriculture. Accessed November 18, 2020. https://entomology.ca.uky.edu/ef218

De Waal, J., A. Malan, and M. Addison. 2011. Evaluating mulches together with Heterorhabditis zealandica (Rhabditida: Heterorhabditidae) for the control of diapausing codling moth larvae, Cydia pomonella (L.) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Biocontrol Science and Technology. 21.3: 255-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2010.540749

IPM Institute of North America. 2020. What is Integrated Pest Management? Accessed November 18, 2020. https://ipminstitute.org/what-is-integrated-pest-management/

Jones, V. 2020. How to Effectively Manage Codling Moth. Washington State University Tree Fruit Research Center. Accessed December 24, 2020. http://treefruit.wsu.edu/article/how-to-effectively-manage-codling-moth/?print-view=true

Jones, V., and J. Brunner. 1993. Degree-Day Models. Washington State University Tree Fruit Research Center. Accessed January 19, 2021. http://treefruit.wsu.edu/crop-protection/opm/dd-models/

Jumean, Z., C. Wood, and G. Gries. 2009. Frequency Distribution of Larval Codling Moth, Cydia Pomonella L., Aggregations on Trees in Unmanaged Apple Orchards of the Pacific Northwest. Environmental Entomology 38.5: 1395-399. https://doi. org/10.1603/022.038.0507

Kaya, H., J. Joos, L. Falcon, and A. Berlowitz. 1984. Suppression of the Codling Moth (Lepidoptera: Olethreutidae) with the Entomogenous Nematode, Steinernema Feltiae (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 77.5: 1240-244. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/77.5.1240

Lacey, L., S. Arthursa, T. Unruha, H. Headricka, and R. Fritts Jr. 2006. Entomopathogenic nematodes for control of codling moth (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) in apple and pear orchards: Effect of nematode species and seasonal temperatures, adjuvants, application equipment, and post-application irrigation. Biological Control 37.2: 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. biocontrol.2005.09.015

Leisso, R. 2019. Bagging apple fruit for simple codling moth control 2019. Montana State University-Western Agricultural Research Center. Accessed November 18, 2020. https://agresearch.montana.edu/warc/research_current/apples/apple_bagging_2019.html

Murray, M., and D. Alston. 2020. Codling Moth in Utah Orchards. Utah State University and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory (ENT-13-06). Accessed November 18, 2020. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curall/880/

Odendaal, D., M. Addison, and A. Malan. 2016. Evaluation of Above-Ground Application of Entomopathogenic Nematodes for the Control of Diapausing Codling Moth (Cydia Pomonella L.) Under Natural Conditions. African Entomology 24.1: 61-74. https://doi.org/10.4001/003.024.0061

Phillips, M. 2011. The Holistic Orchard: Tree Fruits and Berries the Biological Way. Chelsea Green Publishing. White River Junction, Vermont, U.S.A.

Renquist, S. 2018. Fruit Thinning. Oregon State University Extension Service. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/gardening/berries-fruit/fruit-thinning

Skelly, J. 2013. Horticultural Oils – What a Gardener Needs to Know. University of Nevada, Reno, Extension FS-13-20. Accessed November 18, 2020. https://extension.unr.edu/publication.aspx?PubID=3029

USU-Extension. 2018. Codling Moth Spray Dates: Apple, Pear. Fruit IPM Advisory. Accessed January 19, 2021. https://pestadvisories.usu.edu/2018/05/07/cm/

UC-IPM. 2021. Agriculture: Apple Pest Management Guidelines: Codling Moth (Cydia pomonella). Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/apple/Codling-moth/