Recommended Safeguards for Residential Vermiculite (Zonolite) Attic Insulation

The purpose of this guide is to promote awareness of vermiculite (Zonolite) attic or wall insulation, as steps should be taken to minimize contact

Last Updated: 08/20by Terry Spear, PhD, Professor Emeritus, Safety, Health and Industrial Hygiene, Montana Tech; Julie Hart, PhD, CIH, Professor and Department Chair, Safety, Health and Industrial Hygiene, Montana Tech; and Barbara L. Allen, MS, MSU Extension, Associate Specialist

THE FOCUS OF RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY

inspections commonly involves an evaluation of potential human health concerns to home occupants, such as the presence of lead-based paint or asbestos-containing materials in thermal system insulation, ceiling texture, flooring, and siding. However, the presence of another source of asbestos, vermiculite insulation, is not always included in this assessment. Failure to account for the presence of vermiculite insulation in properties may result in serious health risks to occupants, especially if remodeling or other activities occur on the property that may disturb the vermiculite. The presence of vermiculite insulation in homes and other structures should be evaluated and occupants should be warned when vermiculite is identified. Steps should then be taken to minimize contact with this material. The purpose of this guide is to promote awareness of vermiculite (Zonolite) attic or wall insulation.

What is Vermiculite?

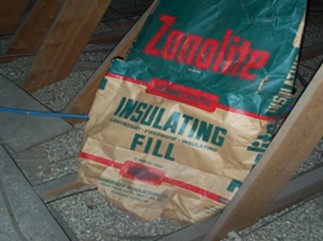

Vermiculite is a silver-gold to gray-brown mineral that is flat and shiny in its natural state and resembles mica. Flakes of this mineral can also range in color from black to shades of brown and yellow. Vermiculite in attic spaces is commonly described as resembling kitty litter or floor dry desiccant material due to its color and granular appearance as illustrated in Figure 1. Some vermiculite granules may appear shiny and the granules will most likely not be as uniformly shaped and sized as kitty litter. When heated to around 1000 degrees Celsius, it pops or expands as illustrated in Figure 2. This expanded form makes the vermiculite suitable for use as insulation, as does the fact that vermiculite has fire-resistant properties.

Figure 1: Zonolite loose-fill attic insulation BY JOHN PODOLINSKI

Figure 2: Vermiculite/Zonolite. BY JOHN PODOLINSKI

Due to its fire-resistant properties, its light weight and expansion capabilities, vermiculite has been extensively used as an insulation material for attics, wall fill, and concrete block. In addition, vermiculite has been used in horticultural products (potting soil), packaging material, and as an aggregate for insulation plasters, fire-resistant insulating wall-boards and acoustic tile. Commercial names for expanded vermiculite include Zonolite™, Unifil™, Porosil™, and Monokote™.

While vermiculite deposits are found and mined in various parts of the world including Australia, Brazil, China, South Africa, and the U.S., the majority (up to 80% of the world’s supply) of vermiculite was mined near Libby, MT, from the early 1920s through 1990 (ATSDR, 2003). Unfortunately, the vermiculite from Libby was contaminated with a type of asbestos referred to as Libby amphibole. The precise number of U.S. homes insulated with Zonolite brand vermiculite attic insulation is unknown; however, vermiculite was widely distributed via processing plants throughout the country and may be present in millions of homes, including thousands in Montana.

Asbestos in Vermiculite

While it is known that vermiculite mined in Libby is associated with asbestos, asbestos contamination in vermiculite mined in other locations within and outside the U.S. has been reported as either not detectable or present at much lower levels than those found in the Libby vermiculite. This is because the desired vermiculite veins in Libby were in close proximity to veins of asbestos and thus when mined, were mixed together. Due to the volume of vermiculite produced from the Libby site, some states assume that if vermiculite is in the attic, it is presumed to contain Libby amphibole asbestos and should be removed. It is important to note that some construction professionals who work in energy conservation programs will not pursue weatherization activities in attics where Zonolite is present.

Vermiculite and Related Health Hazards

Epidemiologic studies among mine and mill workers in Libby, MT demonstrate substantial asbestos-related disease health risks. Asbestos-related diseases include several different illnesses that are associated with inhaling asbestos fibers. These include:

- asbestosis, accumulation of lung scar tissue (collagen);

- mesothelioma, a cancer of the chest wall, lining of the lungs, or abdominal cavity;

- lung cancer; and

- pleural changes, thickening of the lining of the lungs and/ or along the chest wall and diaphragm due to collagen deposits and fibrosis.

These diseases have been identified in former vermiculite mine and mill workers, and within the Libby community among area residents with no direct occupational exposures.

In 2009, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared a public health emergency in Libby, citing rates of asbestosis and mesothelioma in the community that were “staggeringly higher than the national average for the period from 1979–1998.”

Toxicity and Exposure Pathways of Libby Amphibole Asbestos

The primary means by which Libby amphibole asbestos poses a health hazard is through inhaling (breathing) fibers released from vermiculite. Factors such as the amount inhaled, the duration of the exposure (how long an individual is exposed), the toxicity, and the frequency of exposure (how many times an individual is exposed in a lifetime), are the primary factors in predicting disease risk. When inhaled, asbestos fibers have the ability to reach deep regions of the lungs due to their aerodynamic properties. Many of the asbestos-related diseases described previously in this document are derived from the body’s unsuccessful attempt to clear asbestos fibers. As with other asbestos fibers, their durability and persistence lends to their toxicity. Autopsy analyses of lung tissue in deceased individuals have revealed lung asbestos fiber problems decades after exposure. The time from exposure to the onset of disease is referred to as the latency period. Asbestos-related diseases typically have long latency periods, ranging from 10 to 50 years, although shorter latency periods have been reported for Libby amphibole-related diseases. The most important defense against asbestos-related disease is to prevent exposure to airborne asbestos.

Because most people spend significant time in their home environment, asbestos-containing materials in the home, including asbestos-contaminated vermiculite insulation, may present an important, though under-reported, exposure pathway to asbestos fibers. Inhalation pathways from vermiculite insulation may include:

- the disturbance of insulation during remodeling or work in attics and wall cavities (plumbing, wiring, etc.),

- insulation falling or getting carried into living areas within the home through attic penetrations such as light fixtures in the ceiling, ceiling fans, or other cracks in the ceiling, pipes, ducts, wiring and/or conduit, or

- storing items (i.e.; holiday decorations) in an attic containing vermiculite.

Because of their shape and small size, asbestos fibers, especially those small enough to be inhaled, remain airborne for hours when dispersed into the air. Once airborne, asbestos fibers have the ability to drift long distances from their source. In addition, fibers that eventually settle out of the air can be readily dispersed by moving people, pets, minimal air movement, and normal household activities such as sweeping or vacuuming.

Preventing Exposure to Libby Amphibole Asbestos

The most effective strategy in preventing exposure to asbestos in vermiculite is to have it removed by a certified asbestos abatement contractor trained to utilize techniques that prevent living space contamination during removal. (Simply covering the vermiculite insulation with other insulation is not recommended.) When seeking an asbestos contractor, consider collecting at least three bids, verify insurance, and check references before entering into a contract.

Prior to the removal of vermiculite insulation, vermiculite pathways into living spaces should be identified and controlled. Vermiculite insulation has been documented to migrate into and through electrical wiring and conduit, piping, ducting, light fixtures, cracks and wall cavities to other areas in the home. These pathways into home living spaces must be sealed. In addition, measures should be taken to avoid entering the attic space, especially through interior attic entryways. Attic spaces containing vermiculite insulation should never be used for storage. When running wires in an attic, an alternative should be considered to avoid disturbing vermiculite, such as running wires below the ceiling in conduit or behind trim.

Identifying vermiculite before it’s disturbed is critical to avoid exposure. Research has shown that disturbance of certain substances that contain asbestos (soil, vermiculite insulation), can create potentially hazardous exposures. As a result, vermiculite attic insulation should not be disturbed. Prior to home remodeling, the owner should verify whether vermiculite is present. If vermiculite is found, the homeowner should research abatement options such as leaving it alone or removing it properly.

If vermiculite is disturbed accidentally, clean up should include using wet wipes, HEPA filtered vacuuming and other appropriate decontamination actions. Typically, an asbestos contractor will wet wipe and HEPA vacuum the entire workspace after vermiculite removal. This cleaning may need to be repeated. In many cases, vermiculite that has lodged in nooks, crannies, and under attic floor joists gets free after the removal phase. Abatement contractors follow up cleaning phases with application of an encapsulant that “locks down” any fibers and dust. Encapsulants are water- based and are applied with an airless sprayer or weed sprayer. Collected vermiculite waste should be properly packaged and disposed of at a licensed class II landfill. Keep in mind that disposal of asbestos-containing vermiculite is regulated by the Montana Department of Environmental Quality Solid Waste Program rules.

The key recommendations for home occupants to minimize exposure are:

- Do not disturb vermiculite attic insulation. Any disturbance has the potential to release asbestos fibers into the air.

- If occupants must go into an attic space with vermiculite insulation, they should make every effort to limit the number, duration, and activity level of those trips. Boxes or other items should not be stored in attics if retrieving them disturbs the insulation.

- Children should not be allowed to play in an attic with open areas of vermiculite insulation.

- Occupants should never attempt to remove the vermiculite insulation. If removal is necessary, such as during remodeling/renovations, hire professionals trained and certified and/or licensed to safely remove the material.

Sampling and Analysis for Asbestos in Vermiculite

As noted previously, some states assume that if vermiculite is in the attic, it is presumed to contain Libby amphibole asbestos and should be removed if it will be disturbed. Homeowners, potential homebuyers, landlords, etc., may elect to take this same approach, or they may want the vermiculite sampled and analyzed. Although there are several techniques for analyzing asbestos in bulk materials, the accurate determination of asbestos in vermiculite can only be made by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Because asbestos in vermiculite is a contaminant generally present in trace levels, it is critical that appropriate sampling and analytical methods for detecting trace levels of asbestos are employed.

Sampling vermiculite insulation for potential asbestos contamination should be performed by a qualified asbestos inspector identified by the Montana Department of Environmental Quality. These individuals are trained to conduct appropriate sampling procedures for asbestos in vermiculite. In addition, these individuals will be familiar with appropriate personal protective equipment and other measures needed to ensure their safety and the safety of home occupants. A link to qualified inspectors is provided below.

Additional Resources

A consumer-friendly webpage that provides important information on how to protect yourself and your family from suspected vermiculite insulation from Libby, MT.

The U.S. Zonolite Attic Insulation (ZAI) Trust was established in 2014 as a means to partially reimburse qualified homeowners for costs associated with the removal of Zonolite vermiculite insulation and re- insulation, when it is established that the vermiculite insulation came from Libby, MT. The ZAI Trust can reimburse qualified homeowners up to $100 to have vermiculite insulation sampled by a state-licensed asbestos inspector. The test is designed to determine if the vermiculite was sourced from Libby, but it is not a specific test for asbestos. The ZAI Trust also partially covers residential Libby vermiculite removal.

The Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) Asbestos Control Program (ACP) website with a list of contractors.

References

Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry (ATSDR) (2003) Public Health Assessment for Libby Asbestos NPL Site, Libby, Lincoln County, Montana EPA Facility ID: MT0009083840 MAY 15, 2003.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) (2020). Protect Your Family from Asbestos-Contaminated Vermiculite Insulation. Retrieved online January 27, 2020 from: https://www.epa.gov/asbestos/protect-yourfamily-asbestos-contaminated-vermiculite-insulation.