Rush Skeletonweed

Rush skeletonweed is an invasive, non-native perennial forb that can negatively impact range and crop lands. Rush skeletonweed’s presence is limited in Montana so efforts should focus on early detection and rapid response to contain and control reported infestations.

Last Updated: 01/19by Stacy Davis, Research Associate; and Jane Mangold, Associate Professor and Extension Invasive Plant Specialist, Department of LRES

RUSH SKELETONWEED IS AN INVASIVE NON-NATIVE

perennial forb. It is highly branched and has few stem leaves, hence its name “skeletonweed” or “nakedweed.” Rush skeletonweed’s presence is limited in Montana so efforts should focus on early detection and rapid response to contain and control reported infestations.

Species name: Chondrilla juncea L. Family: Asteraceae

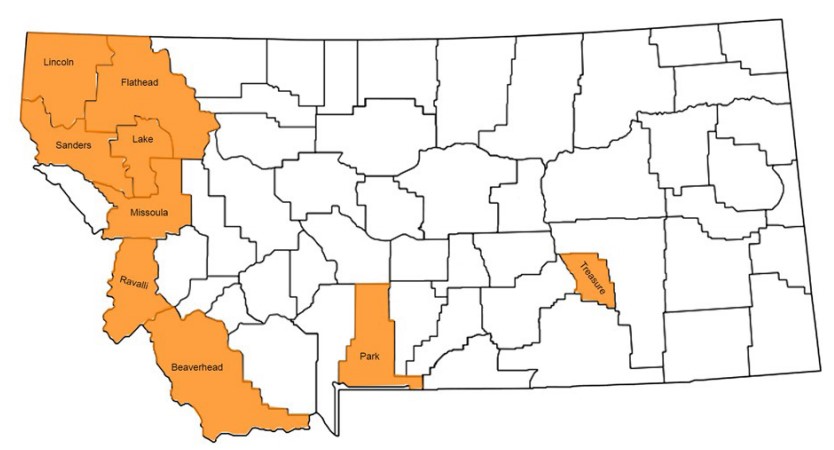

History and status: Rush skeletonweed is native to Asia, the Mediterranean, and North Africa. It was first found in the eastern U.S. in the 1870s and the western states by 1939. It is a noxious weed in nine western states and is a priority 1B noxious weed in Montana. Rush skeletonweed is a relatively new invader to Montana, first being reported in Sanders county in 1987. Rush skeletonweed is estimated to infest 3,300 acres in Montana and has been reported in nine counties (Figure 1).

Identification: Rush skeletonweed is a perennial forb that grows 1-3.5 feet tall. It has a deep, slender taproot and may also have lateral, rhizome-like roots. Dandelion-like rosettes form in the fall and wither as the plant matures the following growing season (Figure 2). Rosettes bolt to form a highly- branched, flowering stem with few leaves (Figure 3). While most parts of rush skeletonweed are smooth, there are stiff, downward pointing hairs on the lower 4-6 inches of each stem – this is a key diagnostic feature (Figure 2). The plant exudes a white, latex sap when cut or broken. Small yellow flowers with many petals form along the stem and branch tips in groups of one to five (Figure 4). Seeds have a parachute of hairs, called a pappus, which aid in wind dispersal (Figure 4).

Not to be confused with: In the rosette stage, rush skeletonweed may be confused with common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale). Prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola) is like rush skeletonweed in that it has stiff hairs on the stem near the base of the plant and exudes a milky sap. However, prickly lettuce is mostly unbranched and has more conspicuous leaves. Rush skeletonweed may also be mistaken for tumble mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum) with its branched structure. However, tumble mustard has four- petaled, pale yellow flowers. Skeleton plant (Lygodesmia juncea) is a native perennial forb that has a similar skeleton- like appearance, but it has pinkish flowers and does not have any hairs on the lower portion of the stem. Native skeleton plant is not invasive and does not pose a threat.

FIGURE 2. Rush skeletonweed basal leaves appear similar to common dandelion, but stems have stiff, downward-pointing hairs. Photo by Matt Lavin, MSU.

FIGURE 3. The “skeleton-like” appearance of rush skeletonweed (many branches with few to no leaves on them) is evident in this grouping of plants. Photo by Clinton Shock, Oregon State University.

FIGURE 4. Rush skeletonweed has bright flowers with bright yellow, narrow petals, and seeds have a pappus to aid in dispersal by the wind. Photo by Steve Dewey, Utah State University, bugwood.org.

Habitat: Rush skeletonweed prefers well-drained, sandy, or rocky soils. It is commonly found growing along roadsides and in pastures, rangelands, or grain fields. It favors disturbed land such as areas subject to drought, overgrazing, or wildfires.

Figure 1. Map of Montana showing counties where rush skeletonweed has been reported: Lincoln, Flathead, Sanders, Lake, Missoula, Ravalli, Beaverhead, Park and Treasure. It was eradicated from Treasure County after being found in 2004. (Compiled records from Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria, EDDMapS West, Intermountain Region Herbarium Network, Montana Natural Heritage Program, and Montana State University Schutter Diagnostic Lab)

Spread: Rush skeletonweed reproduces both by seed and vegetatively. Seeds spread long distances via animals or vehicles and can also spread by wind due to the parachute of hairs on the seed. The seeds have minimal dormancy and usually germinate within one to two years. In addition to a slender taproot, rush skeletonweed has laterally-spreading roots that can produce daughter rosettes. Even small root segments can produce new plants.

Impacts: Rush skeletonweed is primarily problematic in rangelands in the inland Pacific Northwest where it can reduce forage production and plant community diversity. It can also spread into crop fields and is especially problematic in wheat and grain crops in other countries. In Australia, grain yields were reduced up to 80% by rush skeletonweed infestations. Similar losses in small grain yields could be possible in the western U.S. In addition to reducing crop yields, its wiry stems and latex sap can interfere with harvesting.

Management: Since rush skeletonweed has a limited presence in Montana, management efforts should focus on preventing or eradicating new infestations while containing or suppressing larger, established infestations. Maintaining a healthy plant community with limited disturbance can aid in prevention, as well as being aware of the potential for seeds to spread through machinery, livestock, or recreationists. Small infestations can be controlled by diligently hand-pulling plants when the soil is wet and repeating several times a year for several years. Mowing can help reduce biomass and reduce seed production, but it is not effective at eliminating rosettes or harming roots. Tilling or cultivating fields with patches of rush skeletonweed is not recommended because the root fragments can be spread further and develop into new plants. Planting competitive legumes, such as alfalfa, may reduce rush skeletonweed through shading and competition for nutrients. Sheep or goats will eat rush skeletonweed and can be used to reduce or prevent seed production.

There are seven genotypes of rush skeletonweed in North America, and two types are most common in the Pacific Northwest. Each genotype responds differently to management, particularly management with biological control or herbicides.

There are four approved biological control agents for rush skeletonweed. Aceria chondrillae is a gall mite that has variable success depending on the site, plant size, and rush skeletonweed genotype. Puccinia chondrillina is a rust fungus that can decrease plant size and seed production and has been most effective in moist sites with certain genotypes. Bradyrrhoa gilveolella (skeletonweed root moth) is in the first stages of establishment, so efforts are focused on additional releases and monitoring. Cystiphora schmidti is a gall midge that has low priority for redistribution due to issues with high predation and parasitism. Oporopsamma wertheimsteini (root crown feeding moth) and Sphenoptera foveola (root beetle) are being tested as additional biocontrol agents.

Rush skeletonweed control with herbicides is challenging due to deep and extensive roots and limited leaf area which makes it difficult for herbicides to move throughout the plant. Two,4-D acts primarily on aboveground growth and should be applied to rosettes in the spring immediately before or during bolting. Clopyralid (e.g. Transline®), aminopyralid (e.g. Milestone®), and picloram (e.g. Tordon®) provide better control of rush skeletonweed, including roots, than 2,4-D. These herbicides should be applied to rosettes in the fall or spring (prior to bolting and flowering), and repeated applications will be necessary for long-term control. The addition of methylated seed oil can increase herbicide efficacy.

Additional resources

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following reviewers:

- Tyler Lane, Montana State University Extension

- Amanda Williams, Teton County (ID) Weed Control

- Adam Schroeder, Ada County (ID) Weed Control

If you are suspicious that you may have found rush skeletonweed, please contact your local Extension agent or weed coordinator, or the Montana State University Extension Schutter Diagnostic Lab, http://diagnostics.montana.edu.