Estate Planning Tools for Owners of Pets & Companion or Service Animals

This MontGuide outlines legal options for owners who plan to name a caregiver for their companion animals, service animals and/or pets in case of the owner’s death or incapacitation

Last Updated: 06/19by by Jona A. McNamee, former MSU Family and Consumer Science Extension Agent, Cascade County; Marsha A. Goetting, MSU Professor and Extension Family Economics Specialist, Montana State University-Bozeman; and Gerry W. Beyer, Governor Preston E. Smith Regents Professor of Law, Texas Tech University School of Law-Lubbock

WHETHER REFERRED TO AS DOMESTICATED PETS,

companion animals, specialty pets, service animals or as simply pets*, they play an extremely significant role in the lives of many Montanans. By planning ahead and obtaining the appropriate legal documents, owners can ensure their pets (dogs, cats, horses, birds, etc.) will continue to receive proper care if the owner becomes incapacitated and when the owner dies.

* Throughout this MontGuide the word “pet” will be used for brevity.

Planning ahead provides pet owners with peace of mind as they know their pet will be cared for as intended. Family and friends are relieved of the responsibility of making a multitude of decisions about the care of the pet after the death or incapacity of the owner. Pets also benefit from the owner’s planning as they are more likely to experience a smooth transition to a new home and new pet caregiver.

Who gets your pet when you die?

In Montana, a pet is defined as “any domesticated animal normally maintained in or near the household of its owner.” A pet is legally considered as tangible personal property, just like dishes, furniture, or jewelry. When a pet owner dies, pets pass to beneficiaries:

- by provisions in an owner’s will, or

- by directives in an owner’s trust document, or

- by a priority list of heirs contained in the Montana Uniform Probate Code (UPC) (if an owner does not have a will or a trust).

Unfortunately, when the UPC applies and if there are multiple heirs, each of whom legally owns a fraction of the pet, they may end up in court arguing about who gets to “have” the pet or who “has” to take on the many tasks of caring for the pet. Heirs may adamantly refuse to accept these responsibilities. If so, the district judge in the county where the deceased pet owner lived makes the final decision about what happens to a beloved pet. If a willing caregiver is not readily apparent, the pet may be placed in a local animal shelter, or in a worst case scenario may be euthanized.

Who would make a suitable pet caregiver?

The selection of a caregiver for a pet is extremely important. Key considerations include: the willingness to assume the responsibilities associated with caring for the pet; the ability to provide a stable home and proper veterinary care for the pet; the lack of allergies to pets among family members; and the harmonious relationship between the caregiver family members, the pet and other existing pets in the household. If there is more than one pet left to care for after death of an owner, another consideration is whether the potential caregiver is willing to keep pets together that have bonded.

Although it may be a difficult subject to broach, these matters should be discussed with the proposed caregiver so there is no confusion at a later time. The name of the selected caregiver should be documented in writing. The document should be placed in a location that is found easily upon an emergency or the disability or death of the owner, such as a wallet card or taped to the refrigerator.

If there are other pets in the household, consideration should be given to blending of pet families. For example, one common rule of thumb is not to introduce a male cat, neutered or not, into a new household that has existing cats, male or female. The newly introduced cat has a high likelihood of marking territory. This is a concern when introducing a female cat into a household with an existing cat or cats.

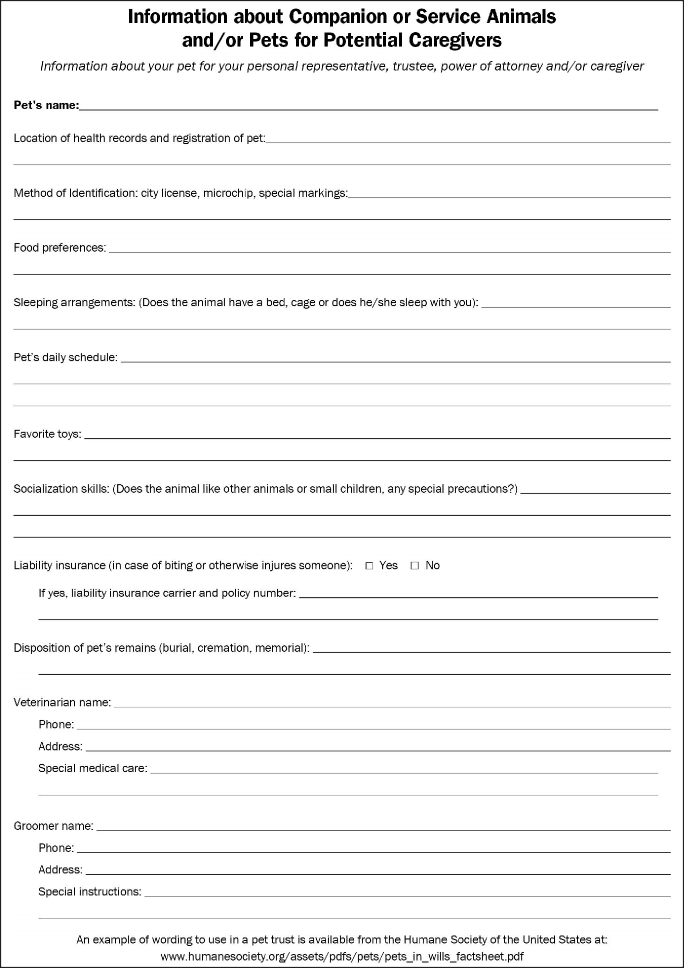

MSU Extension has a checklist “Information for Potential Caregivers about Companion, Service Animals or Pets” in which the owner can describe the characteristics of a particular pet. See page 7.

What types of instructions should be provided?

The pet owner should consult a local veterinarian to suggest ideas specific to the type of pet the owner has. Pet owners can be as detailed as they want about the care of a pet. Examples of the types of concerns about which pet owners may wish to provide instructions include:

- food and diet

- toys

- daily routines

- grooming

- cages

- socialization and behavior

- vaccination and health checkup schedule, including preferred veterinarian

- compensation for the caretaker

- method the caretaker must use to document expenditures for reimbursement

- whether the trust will pay for liability insurance in case the animal bites or otherwise injures someone

- how the trustee is to monitor caretaker’s services

- how to identify the animal, and disposition of the pet’s remains (burial, cremation, memorial).

2ndChance4Pets.org has free materials available for documenting caregivers and care instructions, as well as emergency information wallet cards to identify there are animals in need of care in your home in the event of an emergency.

What legal documents can help assure care of pets?

Pet owners can avoid potential problems by executing legal documents. By expressing their wishes in writing, pet owners can name selected caregivers to care for their pets and outline standards of care. These legal documents include:

- wills

- living or testamentary trusts, and

- durable powers of attorney (financial)

Determining what provisions to include in these legal documents depends on the specific situations and needs of the pet owners and their pets. An attorney who appreciates the sincere desire of the owner to provide for pets can include appropriate directives in legal documents requiring the owner’s heirs and the Montana courts to honor his or her wishes. A local veterinarian could be consulted to assess the health of the pet and make recommendations about care instructions to include in the documents.

How could a will help assure the care of a pet?

A pet owner can provide instructions in a written will giving broad discretion to the personal representative for making decisions about the pet and for using funds from the estate on behalf of the pet. A personal representative is the person named in a will to settle the estate. The terms “executor” or “administrator” were used in Montana prior to the passage of the Uniform Probate Code.

A pet owner may include a provision for a bequest to the personal representative for expenses for finding and transporting a pet to the new home. The owner may direct the personal representative to provide veterinary care needed for maintaining good health and for alleviating suffering of the pet.

A bequest in a will for the benefit of a pet could be for:

- a specific amount (such as $5,000);

- a specific amount up to a certain percentage of the owner’s estate;

- a set percentage of the owner’s estate (such as 10%);

- a set percentage of the owner’s estate not to exceed a certain dollar amount;

- an item of property such as shares of stock.

The bequest for a pet can also be what remains in an owner’s estate after expenses are paid and after bequests to other heirs are distributed. This is termed the residue of the estate. Attorneys often recommend percentages or fractions with minimum and maximums instead of a set dollar amount or the entire residue. This makes the funding provision flexible depending on the amount of money left in the owner’s estate, yet still appropriate for the needs of the pets and desire of the owner.

Bequests can come from a variety of the pet owner’s assets such as: checking/savings accounts; certificates of deposits; U.S. savings bonds; stocks; bonds; mutual funds; and real estate. An owner could also indicate a bequest from the amount from the sale of personal property such as a vehicle, collections of coins, art, or jewelry.

However, there are drawbacks to having a will as the only legal document for the protection of a pet. A will is effective only upon death of the owner, so it does not address pet care during periods of disability or incapacity. Upon death there may be delays before the estate under the will is opened and available to the personal representative to provide pet care expenses.

Probate may result in a long period of time before the owner’s instructions regarding the long-term care of the pet can be carried out. Because a will takes effect only upon the owner’s death, it may not be probated and formally recognized by a Montana district court until months or more than a year after the death of the owner. During this period of time the pet is in limbo without any funds for care.

Another drawback of a will is once the estate is closed, the personal representative no longer has legal authority over the deceased person’s estate to assure that the selected caregiver is carrying out the owner’s wishes for care of the pet. Because of these limitations, attorneys often recommend the creation of a trust for a pet.

How could a trust help assure the care of a pet?

A pet owner may create and fund a pet trust either while he or she is alive (called an “inter vivos” or “living” trust) or upon death by including trust provisions in a will (called a “testamentary” trust). A trust is a legal arrangement by which an individual shifts ownership of property from personal ownership into the legal ownership of the trust. The pet owner names a trustee to manage the funds for the benefit of the pet. The trustee may not use any portion of the principal or income in a trust for any other use other than for those specified by the trust instrument for the pet.

The Montana Uniform Trust Code (MUTC) allows a trust to be created that provides for the care of an animal alive during the settlor’s lifetime (settlor is the legal term for the person who creates a trust). The trust terminates upon the death of the animal. However, if the trust was created to provide for the care of more than one animal alive during the settlor’s lifetime, it doesn’t terminate until the death of the last surviving animal.

Living trust. A living trust takes effect immediately and thus will already be functioning when the pet owner dies or if the pet owner becomes incapacitated.

The Humane Society of the United States provides sample language of a trust at: www.humanesociety. org/assets/pdfs/pets/pets_in_wills_factsheet.pdf

This avoids a delay between the pet owner’s death or incapacity and the funds being available for the pet’s care. If the trust assets are managed by a financial institution or a trustee other than the pet owner, a living trust may have start-up costs and yearly administration fees.

When a pet owner creates a living trust, money or other property is placed in the trust at the time it is created. Additional funds can be added to the trust at a later time. The pet owner should document the transfer and follow the appropriate steps based on the type of property placed in the trust. If the pet owner is transferring money in a trust, he or she would need to set up a checking account and then write a check that shows the payee as, “[name of trustee], trustee of the [name of pet trust], in trust” and then indicate on the memo line that the money is for “contribution to [name of pet trust].”

Testamentary trust. A testamentary trust is a less expensive option because the trust does not take effect until the owner dies and the will is declared valid by the district court. A disadvantage of a testamentary trust is there are no funds available to care for the pet during the gap between when the pet owner dies and when the will is declared valid, the estate closed, and testamentary trust established. In addition, a testamentary trust does not provide protection for the pet if the pet owner should become incapacitated and unable to care for the pet.

If the pet owner creates a trust in his/her will, a provision should be included in the property distribution section that transfers to the trust both the pet and the assets to care for the pet.

Example: “I leave [description or name of pet] and [amount of money and/or description of property] to the trustee, in trust, under the terms of the [name of the pet trust] created under Article [number] of this will.”

A trust document provides the pet owner with the ability to provide detailed directions to the caregiver for the pet’s care. A pet owner may specify who manages the property (the trustee), name the pet’s caregiver (the beneficiary), list what type of expenses relating to the pet the trustee will pay, the type of care the animal will receive, what happens if the beneficiary can no longer care for the animal, and the disposition of the pet’s remains after death. The pet owner may direct the trustee to provide funding for the person who provides care for the pet after the owner dies.

An owner may want to give a trustee the power to remove the pet from the caregiver if, in the opinion of the trustee, the caregiver is not providing the level of care for the pet outlined in the trust document. The trustee could contact a veterinarian to assess the health condition of the pet.

Montana Statutory Pet Trust. A Montana honorary trust for pets is valid for only 21 years, even if an owner writes a longer term in the trust document. Thus, the trust terminates the earlier of 21 years or when the pet dies. Unless indicated in the trust document, the trustee may not use any portion of the principal or income from the trust for any other use than for the care of the pet.

A Montana district judge may reduce the amount of the owner’s property transferred to a pet trust if he/ she determines the amount substantially exceeds what is required for the care for the pet. Unless ordered by a district judge or required by the trust document, no filing, reporting, registration, periodic accounting, or separate maintenance of funds is required of the trustee for a pet trust.

If the pet owner did not designate a trustee in his or her trust document, or if no designated trustee is willing or able to serve, the district judge may name a trustee. The judge may also order a transfer of the trust property to another trustee under the following conditions:

- If such action is required to ensure the funds are used to care for the pet.

- If the pet owner did not name a successor trustee in his or her trust instrument, and the originally named trustee is unable or unwilling to serve.

- If no designated successor trustee agrees to serve or is able to serve.

- Upon the death of the pet and termination of the trust, Montana law directs the trustee to transfer the remaining trust property not utilized for the care of the pet order as directed:

- In the pet owner’s trust document.

- Under the will’s residuary clause (if the pet owner had a written will).

- Under Montana intestate succession statutes to the pet owner’s heirs (if the pet owner did not have a will).

Potential sources of funding for a pet trust. Funds in a trust for the care of a pet after the death of the owner could come from pay on death (POD) designations on financial accounts to the trust or transfer on death (TOD) registrations with the trust as beneficiary for stocks, bonds, mutual funds and annuities. The owner could also direct the trustee in the trust document to sell assets such as a vehicle, a house, or a boat and place those funds in the trust for the care of the pet.

Another source of funding is life insurance. A pet owner may fund a living or testamentary pet trust by naming the trustee of the trust as the beneficiary of a life insurance policy. Or, the pet owner may have a certain portion of an existing policy payable to the pet trust. This technique is used if the pet owner does not have or anticipate having sufficient property to transfer for the pet’s care.

In Montana pets are not considered as a “person” so they cannot be named as a beneficiary of a life insurance policy. Pet owners should consult with an attorney and/or life insurance agent about the correct way of naming the trustee of a pet trust as a beneficiary of a life insurance policy. A pet cannot be named as a payable on death (POD) beneficiary on accounts at financial institutions or on a transfer on death registration (TOD) beneficiary on stocks, bonds, or mutual funds.

A pet owner may use life insurance and financial account assets to fund both the living and testamentary trusts by naming the trustee of a pet trust as the recipient of a designated portion or amount of these assets. A pet owner should consult with his or her attorney about the correct way of naming the trustee of the pet trust as the recipient of these funds.

Amount of money in a trust. The amount of money needed to provide adequately for pet care after the owner dies depends on many factors such as: the type of animal, the animal’s life expectancy (especially important in the case of long-lived animals such as a macaw parrot that can live up to 80 years); the standard of living the owner wishes to provide for the animal; the need for potentially expensive medical treatment; and whether the person caring for the pet is to be paid for his/her services.

The pet owner also needs to decide if funds are to be allocated to provide the pet with proper care when the caretaker is on vacation, out of town on business, receiving treatment in a hospital, or is otherwise temporarily unable to personally provide for the pet.

The size of the pet owner’s estate must also be considered. If the estate is relatively large, a pet owner could transfer sufficient property to the trust so the trustee could make payments primarily from income and use the principal only for emergencies for the pet. On the other hand, if the estate is small, the pet owner may wish to transfer a lesser amount and direct the trustee to supplement trust income with withdrawals from the principal as needed.

Naming a Trustee. The trustee for a pet trust needs to be an individual or corporation that a pet owner has the confidence to manage the property in the trust prudently and make sure the caregiver beneficiary is doing a good job taking care of the pet. A family member or friend may be willing to take on these responsibilities at little or no cost. Another option is a professional trustee or corporation that has experience in managing trusts even though an annual trustee fee will need to be paid.

Serving as a trustee can be a potentially burdensome position with many responsibilities. A pet owner should visit with the potential trustee to be sure he/she is willing to do the job when the time comes.

A pet owner should consider naming at least one; preferably two or three, alternate trustees in case the first choice is unable or unwilling to serve. If the potential trustee does not want to serve as the caregiver for the pet, a local veterinarian could be consulted to suggest an alternative.

To avoid having a pet without a home, an animal protection organization such as the Humane Society or a “no-kill animal shelter” could be named as a last resort trustee.

How could a durable financial power of attorney help assure the care of a pet?

Durable powers of attorney, in which a person authorizes someone else to conduct certain acts on his or her behalf, is a standard financial planning tool. The document can be written to be effective upon a pet owner’s physical or mental incapacity.

Provisions can be written in the durable financial power of attorney document authorizing the agent, also called an attorney-in-fact (the person designed to handle the owner’s affairs), to utilize funds or other property as may be necessary to provide for the health, care, and welfare of the pet. A pet owner can also authorize payment to the pet caregiver in the document. Many of the same details for care of the pet outlined in a trust could be applied to a financial power of attorney. The financial power of attorney could even reference and incorporate the terms of a living or testamentary trust.

Because durable financial powers of attorney cease at the death of the pet owner, he/she may want to consider a pet trust to provide for the continuing care for a pet after the owner dies.

For more information about a financial power of attorney read MSU Extension Montguide, Power of Attorney (financial) (MT199001HR).

How to prove my pet’s identity?

To prevent fraud, pet owners should clearly identify pets that are to receive care under a will, trust, or power of attorney. There are a variety of methods that may be used to prevent fraud. A detailed description should include any unique characteristics such as blotches of colored fur and scars that can be included in the legal document. Veterinarian records and pictures of the animal may also be helpful. A more sophisticated procedure is to have the veterinarian or breeder implant a micro-chip in the pet or obtain a DNA sample for later identification purposes.

Summary

In the confusion that occurs when a companion/service/ pet owner becomes incapacitated or dies, pets are sometimes forgotten, sent to a boarding kennel, given to a friend or relative who really does not want another pet, or brought anonymously to a shelter. Planning ahead offers the assurance that a beloved pet is well cared for after the incapacitation or death of the pet owner. By identifying in writing and using a pet trust, a will, and durable financial power of attorney, you have the practical and legal assurances that your pet will be protected if you are no longer able to provide care.

Additional Resources and References

American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA)

- Pet Trust Primer: https://www.aspca.org/pet-care/pet- planning/pet-trust-primer

- Planning for the Pet’s Future: https://www.aspca.org/ pet-care/pet-planning

Animal Legal and Historical Center

- The Michigan State University College of Law maintains a website that is designed to provide pet owners with legal information. Also provided are related links and research papers: https://www. animallaw.info/intro/wills-and-trusts

Committee on Animal Law, New York City Bar

- Providing for Your Pets in the Event of Your Death or Hospitalization. http://www2.nycbar.org/pdf/report/ uploads/8_20072453-ProvidingforYourPetintheEvent ofDeathHospitalization.pdf

Humane Society of the United States

- Providing for your Pet’s Future contains a six-page fact sheet, wallet alert cards, emergency decals for windows and doors and caregiver information forms: www.humanesociety.org/assets/pdfs/pets/pets_in_wills_ factsheet.pdf

Montana Code Annotated

- § 72-38-408; § 72-31-302 – 340; § 72-2-1017; § 80-9-101

Second Chance for Pets

State Bar of Montana

- Norcott, Garrett. What to do with Lassie when Timmy dies from falling down the well? Montana Lawyer, December 2013 Vol. 39 No. 3. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.montanabar.org/resource/collection/ EAA30F23-4767-49DA-BBE7-152CF93C8535/December2013January2014MTLawyer.pdf

Texas Tech University School of Law

- Beyer, Gerry W. Estate Planning for Non-Human Family Members. 2016. www.professorbeyer.com/ Articles/Animals.html

Disclaimer

This publication is not a substitute for legal advice. Rather it is designed to inform persons about estate planning for their companion animals/service animals and pets. Future changes in laws cannot be predicted and statements in this fact sheet are based solely on the statutes in force on the date of publication.

Acknowledgement

Representatives from the following reviewed this publication and recommend its reading by Montana residents who are in the process of developing an estate plan for their pets:

- Business, Estates, Trusts, Tax and Real Property Section – State Bar of Montana

- Texas Tech University School of Law – Lubbock, Texas

We also appreciate the suggestions provided by veterinarians and owners of pets, companion and service animals.