Management of Lice on Livestock

Cattle lice are an important winter season pest of livestock. Sucking and chewing lice can reduce the performance of livestock by lowering weight gains, feed efficiency and overall health of the animal. This guide provides basic lice information and chemical control options for preventing these ectoparasites from becoming established.

Last Updated: 06/21by Gregory Johnson, Professor Veterinary Entomology; revised by Megan Van Emon, MSU Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

THERE ARE APPROXIMATELY 5,000 KNOWN species of

lice that parasitize wild birds and mammals, feeding on blood (sucking lice), skin, hair or feathers (chewing lice) of a host. Most species are considered unimportant from a medical or veterinary perspective. However, lice populations can occur by the thousands or even tens of thousands on an animal. The biting and feeding activity of lice is often irritating, and heavy infestations can compromise the production and vitality of animals.

Lice are generally most abundant on livestock during the winter and early spring when animals are under stress from cold weather, have inadequate nutrition, are infested with internal parasites or have a suppressed immune system. The interaction of these conditions with moderate to heavy lice infestations may result in poor feed efficiency, lower weight gains and milk production, slow recovery from disease, anemia, and general unthriftiness. The presence of lice causes animals to be restless and agitated; they will rub, scratch and lick excessively to get relief from the ectoparasites. The most obvious signs that livestock are infested with lice include hair rubbed off from scratching, blood-stained hair or wool, and faces with a bluish/grayish appearance (especially on white-faced animals). The presence of lice can easily be determined by a close-up examination of the animal. Treatment of animals as described in this MontGuide will eliminate lice as a competing factor for livestock production and health. Alternating active ingredients on an annual basis will allow for better control of lice populations.

General Biology and Life Cycle

Lice that infest livestock are categorized as biting or sucking based on their mouthparts. The mouthparts of biting lice are designed to bite or scrape the skin or sever small pieces of hair or feather to ingest. Sucking lice have piercing-sucking mouthparts that pierce the skin, penetrate a blood vessel and then suck blood through a straw-like channel.

Adult lice are small (1/16–1/8 inch), wingless and flat-bodied. They spend their entire life on the host. Male and female lice feed on the host, mate, and the female cements eggs or nits individually to animal hairs. Females deposit about one egg per day and can live for about 35 days. Egg incubation takes 4 to 15 days before the nymph hatches and each nymphal stage lasts 3 to 8 days. Life cycles are generally completed in 3 to 4 weeks. Lice are unable to survive prolonged periods (a few days) off the host. They have developed specialized structures (claws, hooks and spines) that enable them to attach and stay on the host. Sucking lice have legs that are modified into claws allowing them to grasp and hold onto hairs. Biting lice have grooved antennae that can encircle a host hair to facilitate attachment. Both biting and sucking lice have hooks and spines in various arrangements on their body that also aid in host attachment.

Lice are transferred from one animal to another by direct contact usually when animals are being fed, worked, shipped, or when using a common scratching post. A herd can be re-infested when untreated replacement animals are purchased and added to the herd or stray animals join a herd or flock, or when the duration of the insecticides wanes versus the life cycle of the lice. Nose to nose contact by livestock sharing a common fence can be sufficient for spread of these insects, especially during the winter when infestations are greatest and occur on the head and face.

Louse densities on domestic livestock peak during late fall, winter and early spring and decline during the summer. These seasonal population declines have been attributed to shedding winter coats, and weather factors such as intense summer heat, sunlight or desiccation. In the summer, a few lice persist on animals by moving to protected areas in the folds of skin protected from high temperatures and sunlight. Older cows or bulls are the most likely animals to carry lice during the summer months.

Cattle Lice and Control

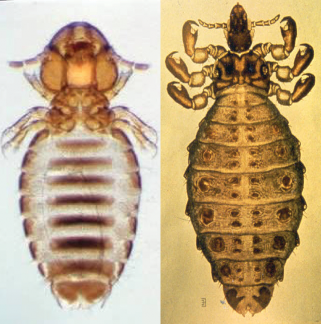

There are four species of lice, one biting and three sucking, which can occur on beef and dairy cattle in Montana at any one time. The cattle biting louse, Bovicola bovis, is one of the most common species found on cattle in Montana (Figure 1). They have a broad reddish head and a pale brown abdomen with slightly darker brown stripes. Adult females are about 1/16 inch in length. This species obtains nourishment for energy and egg production by feeding on skin, scurf (like dandruff) and hair of the animal. Biting lice are frequently found on the top line of the back, especially the withers area and will spread to the poll and tail head.

Three species of sucking lice are found on cattle: the longnosed, Linognathus vitulii, the little blue, Solenopotes capillatus, and the shortnosed, Haematopinus eurysternus. These three species obtain nutrients for energy and egg production by feeding on blood from the animal. Female longnosed cattle lice are about 1/10 inch in length with males slightly smaller (Figure 1). This species infests calves more frequently than mature animals. The preferred infestation sites are the shoulder, back, neck and dewlap. Morphologically, the second and third pair of legs are larger than the first and end in large claws for grasping.

Figure 1. (left) Cattle biting louse: note reddish color with dark bars at each abdominal segment and rounded head. Longnosed sucking louse. (right) Note narrow, pointed head and claws for grasping hair.

The little blue louse is the smallest of the sucking lice; mature females are approximately 1/16 inch in length. Little blue lice occur in clusters on the face, especially around the eyes and muzzle. Heavy infestations give the animal a bluish appearance which is especially obvious on white-faced animals (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Yearling calf heavily infested with little blue cattle lice. Note bluish appearance as a result of presence of lice on muzzle and cheek.

This species and the longnosed cattle louse are the two most common species found on cattle in Montana.

The shortnosed cattle louse is the largest found on cattle in the northern U.S. with females averaging about 1/8 inch in length. Infestations occur on the neck, dewlap and brisket. This species has prominent projections (ocular points) on the side of its head and the three pairs of legs are of equal size. This is the least common species of cattle lice to occur in the Rocky Mountain region.

CONTROL

Many insecticide formulations and application methods are available for cattle lice control. The most popular application method is a pour-on because of the ease of application and reduced stress when treating animals. To apply a pour-on, the correct amount of insecticide, based on animal weight, is poured along the midline of the back of the animal starting at the withers, unless using a product that has residual effect to kill the unhatched eggs which requires the top of the poll and neck to have one- third of the application with the remaining dose applied along the back. This ensures the long acting or residual effect of the IGR (Insect Growth Regulator) that kills eggs. Insecticide dust applied through a dust bag will provide some control of cattle lice but will not eradicate lice on the animal. Dust bags work best when they are placed where cattle will use them daily (e.g., entrance to water tank, gateways). Dust bags need to be checked weekly and periodically re-charged with dust. Liquid insecticides used for backrubbers or oilers will also suppress lice densities provided the backrubbers are re-charged with a mixture of diesel + insecticide. Certain insecticide ear tags applied in the fall will control biting lice.

Active ingredients in insecticides for lice control include pyrethroids, avermectins and spinosad. The most common active ingredient in many pour-ons is a pyrethroid, such as cypermethrin, permethrin, or cyfluthrin, and several products contain the synergist, piperonyl butoxide, to increase insecticide activity. These non-systemic insecticides last for several days. However, they do not kill the eggs, thus two applications are required 14 days apart for optimal lice control. The second application will kill newly hatched nymphs. Most pyrethroids are ready-to-use (i.e., do not require mixing) and can be applied to beef and dairy cattle. An exception is Saber Pour-on (lambda-cyhalothrin) which is labeled for use only on beef cattle. Additionally, Clean Up II is also labeled to kill louse eggs, which can lead to a single treatment being more effective. See Table 1 for a list of insecticides and the labeled species.

Avermectins are systemic insecticides that are derived from a soil microorganism, Streptomyces avermitilis. Avermectins include patented and generic compounds (ivermectin, moxidectin, doramectin, eprinomectin and generic ivermectins) that are formulated as pour-ons or injections. Pour-ons are effective against sucking and biting lice on beef cattle. The avermectin products tend to cost more than pyrethroid pour-ons but they control a number of internal parasites (cattle grubs, roundworms and lungworms). Days to slaughter vary by product and applicators should check the label before applying.

Injectable avermectins are only registered for use on beef cattle and are effective against sucking lice only. Producers using injectable avermectins in the fall will likely need to apply a non- systemic insecticide for biting lice control.

Spinosad is derived from a soil-dwelling bacterium, Saccharopolyspora spinosa, and is effective against sucking and biting lice. It has low mammalian toxicity and can be used on beef and dairy cattle. Spinosad is non-systemic and requires two applications 45–60 days apart for maximum lice control.

Representative insecticides for controlling biting and sucking lice may be found in Table 1. Insecticides are listed by chemical class with active ingredients, trade names, application methods, and species.

Horse Lice and Control

Two species of lice, one biting and one sucking, occur on horses, donkeys, and mules in the Rocky Mountain region. Although these species are not as common as cattle lice, infestations may reduce the vigor of the animal or predispose them to diseases. In addition to being spread by animal-to-animal contact, horse lice can be transmitted through grooming equipment and blankets.

The horse biting louse, Bovicola equi, similar in appearance to the cattle biting louse, is generally more common than the horse sucking louse. This species is about 1/10 inch in length and typically infests the neck, flanks, and tail base where it prefers to lay its eggs. These lice feed on skin, hair and skin secretions.

Signs of a biting louse infestation include a scruffy or rough hair coat and excessive rubbing or scratching.

The sucking louse, Haematopinus asini, infests coarse hair, especially the forelock, mane, base of the tail and on hairs just above the hoof. It’s about 1/8 inch in length and is slate gray. The shape of the body and head is similar in appearance to sucking lice species found on cattle. Sucking lice infestations can result in scratching, rubbing and biting at the infested areas.

CONTROL

Insecticides for controlling lice on horses are available as body sprays, wipe-ons or dust (Table 1). Look for age restrictions on the insecticide label as some products or application methods should not be used on foals under three months of age. Body sprays are mixed and applied by a hand pressurized sprayer or mist sprayer. Thoroughly cover the animal but avoid getting the product into horse’s eyes and other sensitive areas such as the mouth or nose. It is recommended to use a piece of clean, absorbent cloth (Turkish toweling) or sponge to apply insecticide to the facial area. A second treatment 14–21 days later is recommended. Insecticide dust can be applied by shaker can or dusting glove. The personal protective equipment (PPE) that should be worn when handling and applying insecticides includes: long sleeved shirt, long pants, shoes and socks, chemical resistant (waterproof or rubber) gloves and safety glasses or other appropriate eye protection.

Sheep Lice and Control

Three species of lice can occur on sheep and goats: the African blue louse, Linognathus africanus, the sheep foot louse, L. pedalis, and the sheep biting louse, Bovicola ovis. The sheep biting louse, while considered the number one louse problem on domestic sheep worldwide, is uncommon, if not absent, in the Rocky Mountain States. It is similar in both appearance and feeding behavior to other biting lice found on livestock.

The sheep foot louse is widely distributed in North America. Light infestations of this species occur as small colonies of lice between and around the accessory digits. In heavy infestations not only the legs support heavy numbers of lice but also the scrotum of rams. This louse is not considered very injurious since feeding occurs on the hairier parts of the sheep’s body and the animal exhibits little discomfort. In severe infestations, however, it may cause some lameness.

The African blue louse is established in sheep producing regions in the southwestern and western U.S. where it has become a major pest of sheep and has been reported on goats. Currently, this is the only louse species of economic importance in Montana. Female lice are 1/10 inch in length and males are slightly smaller. Infestations in the winter can be found on the rib and shoulder areas of sheep. Lambs and yearlings are more susceptible to lice than older animals with heaviest infestations occurring in animals in these age groups that are under stress from poor nutrition or disease. Heavily infested sheep in full fleece can have large patches of blood-stained wool which is bloody fecal material from the lice (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Blood-stained wool caused by an infestation of African blue lice. Scouring of the wool will not remove the stain.

CONTROL

Sheep susceptibility to lice can vary among individuals within a flock, so only a few animals may appear to be infested. Because other animals may be carrying low levels of lice which will serve to re-infest the flock, it is recommended that all animals in a flock be treated. It is also important to treat replacement animals to prevent a new infestation from being introduced. For optimum lice control with spray and pour-on products, manufacturers recommend a second application 10–14 days after the first treatment. The pour-on insecticides listed in Table 1 are oil-based and may leave an oily residue on the wool. Insecticide dust can be applied by shaker can, dusting glove or mechanical dusting applicator.

Carefully read and follow the insecticide label concerning the application of any insecticide to livestock. Due to constantly changing labels, laws and regulations, MSU Extension can assume no liability for the suggested use of chemicals contained herein. Pesticides must be applied legally, complying with all label directions and precautions on the pesticide container and any supplemental labeling and rules of state and federal pesticide regulatory agencies.

Table 1. Insecticides for lice control on livestock.

Active Ingredients1 |

Trade Name |

Chemical Class2 | Application Method3 | Species |

| Doramectin | Dectomax | A | PO, I | Beef cattle, swine |

| Moxidectin | Cydectin | A | PO, I | Cattle |

| Eprinomectin | Eprinex | A | PO | Cattle |

| Ivermectin | Ivermectin | A | PO | Cattle |

| Ivermectin | Ivomec | A | PO, I | Cattle, swine |

| Eprinomectin | Eprizero | A | PO | Cattle |

| Ivermectin | Bimectin | A | PO, I | Beef cattle |

| Ivermectin | Noromectin | A | PO, I | Cattle |

| Coumaphos | Co-Ral | OP | D | Cattle, swine |

| Phosmet | Prolate/Lintox-HD | OP | S, BR | Cattle, swine |

| Coumaphos | Co-Ral | OP | S, BR | Cattle, swine, horses |

| Permethrin | Prozap Insectrin | P | D | Cattle, swine, horses |

| Zeta-cypermethrin/PB | Python | P | D | Cattle, sheep, goats, horses |

| Permethrin | Revenge Dust-On | P | D | Cattle, swine, horses |

| Permethrin | Boss | P | PO | Cattle, sheep |

| Permethrin | Brute | P | PO, BR | Cattle, horses |

| Diflubenzuron/Permethrin | Clean-Up II | P | PO | Cattle, horses |

| Cyfluthrin | Cylence | P | PO | Cattle |

| Permethrin/PB | Permectin CDS | P | PO, BR, S, WO | Cattle, sheep, horses |

| Permethrin | Permethrin 1% | P | PO, BR | Cattle, sheep |

| Permethrin/PB | Revenge Pour-On | P | PO, BR | Cattle, sheep, horses |

| Lambda-cyhalothrin | Saber | P | PO | Beef cattle |

| Gamma-cyhalothrin | StandGuard | P | PO | Beef cattle |

| Permethrin/PB | Synergized DeLice | P | PO, BR | Cattle, sheep |

| Permethrin/PB | UltraBoss | P | PO, BR | Cattle, sheep, goats, horses |

| Lambda-cyhalothrin/PB | UltraSaber | P | PO | Beef cattle |

| Permethrin | GardStar 40% EC | P | S, BR | Cattle, swine, sheep, goats, horses |

| Permethrin | Prozap Insectrin X | P | S, BR | Cattle, swine, sheep, goats, horses |

| Permethrin | Atroban 11% EC | P | BR, S | Cattle, sheep, goats, horses |

| Spinosad | ExPO Extinosad | S | PO | Sheep |

1PB = Piperonyl butoxide

2Chemical Class: A=avermectin, OP=organophosphate, P=pyrethroid, S=Spinosad

3Application Method: BR=backrubber, D=dust, I=injectable, PO=pour-on, S=spray, WO=wipe-on