Saltcedar (Tamarisk)

Species of saltcedar are non-native shrubs or small trees that are invading Montana's waterways. This MontGuide describes saltcedar biological and ecological characteristics. It also provides a variety of management options to control these species.

Last Updated: 12/17by Robert T. Grubb, former Research Associate, Dept. of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences; Roger L. Sheley, former Noxious Weed Specialist; and Ronald D. Carlstrom, Gallatin County Extension Agent Revised by Jane Mangold, Extension Invasive Plant Specialist; and Erik Lehnhoff, Assistant Research Professor, Dept. of Land Resources and Environmental

SALTCEDAR OR TAMARISK

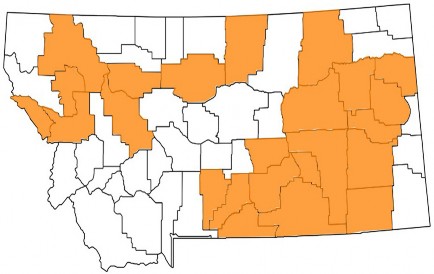

(Tamarix ramosissima, T. chinensis, or T. gallica) is a large shrub or small tree that was introduced to North America from the Middle East in the early 1800s. This weed has been used for ornamentals, windbreaks and erosion control. By 1850, saltcedar had escaped from these areas and infested many river systems and drainages in the Southwest – often displacing native vegetation. Saltcedar continues to spread rapidly and currently infests water drainages and wet areas throughout the United States. It is listed as a noxious weed in Montana and neighboring states. Saltcedar was first found in Montana around 1960 in the Yellowstone and Big Horn River drainages. As of 2017, saltcedar has been reported in 24 counties in Montana (Figure 1). Most of the saltcedar found in Montana is a hybrid of Tamarix species.

FIGURE 1. Counties in Montana where saltcedar has been reported. Compiled records from INVADERS Database System, EDDMapS West, Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria, Intermountain Region Herbarium Network, and MSU Schutter Diagnositic Lab.

Identification and Biology

Saltcedar, a member of the Tamaricaceae family, is classified as either a large shrub or a small tree (Figure 2, page 2). It has numerous slender branches covered with small scale-like leaves that resemble cedar leaves (Figure 3, page 2). Even though leaves resemble cedar leaves, this plant is deciduous. Saltcedar can grow 30 feet tall and has smooth, reddish- brown bark which becomes furrowed and ridged with age. Saltcedar produces thousands of small, five-petaled white to pink flowers throughout the spring and summer (Figure 3). Flowers grow in long, drooping, narrow clusters that are up to three inches long. A mature saltcedar plant can produce half a million seeds each year. Seeds are small and black with a tuft of hair attached to one end, enabling them to float long distances on the wind and water. Seeds are generally short-lived and germination can occur within 24 hours of dispersal under suitable conditions. Most seeds live less than a week in warm or hot conditions, but they can remain viable for more than six months under cool dry conditions. In addition to reproduction by seed, saltcedar can reproduce vegetatively due to a primary root with extensive secondary root branching (Figure 4, page 3). Individual trees generally send up numerous vegetative shoots, creating large clones.

Impacts

Some early studies (pre-1990) indicated that saltcedar uses more water than native riparian species, and it was believed to increase water losses through evapotranspiration. However, recent studies using improved methods for estimating evapotranspiration have shown that saltcedar does not use more water than native vegetation. Thick stands of saltcedar may present other problems though. High densities of saltcedar can congest river channels and create potential flood hazards. Saltcedar also reduces channel widths by decreasing the water velocity and thereby increasing sediment deposition.

FIGURE 2. Mature saltcedar plant. Photo credit: Patricia Gilbert, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

FIGURE 3. Branch showing leaves and flowers of saltcedar. Photo credit: Matt Lavin, MSU.

Research from the southwestern U.S. indicates that native vegetation may decrease in saltcedar-infested areas, but research in Montana showed no differences in plant community composition or species richness in infested versus non-infested areas. Instead, species differences may be more associated with water flow regimes being altered by dams than saltcedar invasion. However, saltcedar infestations in Montana are often younger than those in the Southwest and may not have had time to negatively affect plant communities. It has been suggested that where infestations become very dense, saltcedar may prevent native species from reestablishing by exuding salts from the leaves which increases soil salinity. Native species such as cottonwood are more competitive than saltcedar, and if they can establish, they will eventually overtop and outcompete saltcedar, which is not shade tolerant.

Saltcedar has limited usefulness for animals. Dense stands are unsuitable for many mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and certain groups of birds, such as timber drillers and cavity nesters. However, the southwestern willow flycatcher, an endangered bird, nests in saltcedar in some regions of the western U.S. Mixed stands of native vegetation and saltcedar can provide excellent habitat for many species.

Management

Several methods have been investigated to control saltcedar. In many cases, only temporary suppression of plant growth will be obtained, unless all of the subsurface root crown is destroyed. Remaining root crowns regrow vigorously and will require retreatment. In addition, other invasive plants, like houndstongue, Canada thistle and whitetop often invade a site following saltcedar control. For that reason, follow-up monitoring to control other invasives and/or reinvading saltcedar is critical. Depending on the site and degree of infestation, revegetation with appropriate desirable vegetation, especially riparian shrubs and trees like willows and cottonwoods, may be necessary.

Controlling young, small saltcedar usually involves applying herbicides to foliage, cut stumps, or basal bark. Light infestations of saltcedar in areas without native shrubs and trees may be treated with a foliar application of imazapyr (Arsenal®) at a rate of one pint/acre plus glyphosate (Roundup®) at a rate of two quarts/acre. These herbicides are non-selective and can damage native vegetation. Foliar applications of these herbicides are not recommended in areas where native vegetation may be affected. In such cases, a cut-stump or basal bark treatment may be a better option.

The cut-stump method involves cutting the stems within two inches of the soil surface using a chainsaw or mechanical shears, applying herbicide on and around the perimeter of the stump within a few minutes, and retreating any resprouts four to 12 months following initial treatment. The cut-stump method is most effective on larger stems and is typically performed in the fall. Triclopyr can be applied to the cut stumps as undiluted PathfinderII® or a 50 percent solution of Garlon®. Imazapyr (Arsenal®) is effective when applied to cut stumps at a rate of 12 ounces/gallon of water. Undiluted glyphosate (Rodeo® or Roundup®) can be applied to the cut stumps as well.

FIGURE 4. Saltcedar has a large primary root and branching secondary roots. Photo credit: Patricia Gilbert, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Basal bark treatment involves applying herbicide to the lowest 18 inches of intact stems. Herbicides must be applied to the entire circumference of every stem in order to be effective. This method works best on stems smaller than five or six inches in diameter. Triclopyr can be applied as undiluted PathfinderII® or a 20-30 percent solution of Garlon® or Remedy®. Because saltcedar generally grows in wet areas, caution should be used when applying herbicides to keep them out of ground and/or surface water. Triclopyr and imazapyr should not be applied directly to open water or below the mean high water mark. Furthermore, use caution when applying to permeable soils where a shallow water table is present. Be sure to read and follow the label when applying herbicides to manage saltcedar.

Root plowing is a mechanical tool that has been successful in managing saltcedar infestations. It is quite disruptive, however, and should only be used in severe infestations and as part of an overall site reclamation project. Root plowing involves pulling a plow, set 12 to 18 inches below the soil surface, through an infestation to cut the root crowns. Some roots may be up to three feet deep due to deposition of sediment on top of the plant, so plows may have to be set quite deep. If the root crown is removed, the plant will not be able to sprout again and form new plants. For root plowing to be effective, the above-ground vegetation should be piled and burned to prevent resprouting of shoots. If properly performed, root plowing can achieve 90 percent control of saltcedar stands in the field. Root plowing during hot and dry weather can improve the effectiveness of this control method.

Manipulating water levels may influence saltcedar populations. For example, a study in Montana only found young plants (<3 years old) in the drawdown zone of Fort Peck Reservoir and suggested three months of inundation may kill saltcedar plants. Doing so may prevent development of dense stands of saltcedar in this zone and limit seed production. However, this process may need to be repeated approximatively every five years to limit saltcedar establishment.

Biological control agents are not currently approved for use on saltcedar in the United States. While the Mediterranean tamarisk beetle (Diorhabda elongata) has been very effective in controlling saltcedar in the southwestern U.S., further transport and release of the beetles have been suspended due to concerns over potential effects to the critical habitat of the federally- listed, endangered southwestern willow flycatcher, which nests in saltcedar. The beetle has been previously released in Montana, but has not yet established in sufficient numbers, perhaps due to high levels of predation, increased plant resource availability, or other factors currently being researched.

This information is for educational purposes only. Reference to commercial products or trade names does not imply discrimination or endorsement by Montana State University Extension.