Who Gets Grandma’s Yellow Pie Plate? Transferring Non-Titled Property

The transfer of non-titled property such as photographs and other family heirlooms often creates more challenges among family members than the transfer of titled property. Here's how to deal with some of the issues that may arise.

Last Updated: 03/23by Marlene S. Stum, Ph.D., Family Economics & Gerontology, University of Minnesota; and Marsha A. Goetting, Ph.D., CFP®, CFCS, Extension Family Economics Specialist, Montana State University

“This is no ordinary yellow pie plate. This actually belonged to my great-grandmother who spent a lot of time in the kitchen with her daughters baking pies. The tradition of baking pies has continued on through the generations and the yellow pie plate is always on the table at family gatherings. The pie plate holds a lot of special memories for my family. Who gets Grandma’s yellow pie plate when she dies?” – Andrea

MOST PEOPLE HAVE PERSONAL BELONGINGS such as wedding photographs, a baseball glove or a yellow pie plate that have special meaning for them and other family members. These types of personal possessions, as well as jewelry, stamps, gun and coin collections, quilts or sports equipment, are referred to as non-titled property because there are no legal documents (such as titles) to indicate who officially owns them.

What happens to your non-titled personal belongings when you die? Who decides who gets what? Planning for the transfer of personal belongings is a challenge facing owners of the items and, potentially, family members and the personal representative who are left to make decisions about the items when a family member dies.

Non-titled property may or may not have financial value, but often has sentimental, historical or emotional value both for the giver and receiver. Many people are familiar with the need to make decisions regarding the distribution of a home, savings account or vehicle when they die. In many cases, however, non-titled property is not included in the decision- making process.

Decisions about what to do with a person’s belongings often are not made during ideal circumstances. Frequently these decisions are made in times of family crisis, such as when a death has occurred or when an elderly family member moves to a health care facility. The process becomes more challenging and sensitive if family members are left to make the decisions when they are grieving over the loss of a relative, selling the home in which they grew up, and/or facing the increasing dependence of an older adult. While not easy, making decisions about the transfer of personal property can be an opportunity for family members to reminisce, share memories and work through the grieving process.

The transfer of non-titled property is an issue that impacts individuals regardless of their financial worth, heritage or cultural background. What surprises many people is that often the transfer of non-titled personal property creates more challenges among family members than the transfer of titled property. Why? Personal belongings usually have different meanings for each individual. The sentimental value or meaning attached to the personal property often may be more important than the financial or dollar value. Dividing items with sentimental value fairly or equitably to all parties can be very difficult.

People commonly have different perceptions of what is a fair process and what are fair results. Talking about one’s possessions may be more personal than talking about other types of financial assets. Facing one’s own death, as well as the death of family members, can be emotionally draining.

Understand the Sensitivity of the Issue

If you are a son or daughter who feels the need to talk with Mom or Dad or Grandma or Grandpa regarding the distribution of their personal property, beginning the conversation may be the most difficult part. Here are several suggestions on ways to start a conversation about this sensitive issue.

Ask “what ifs.” For example, you could say, “Dad, have you given any thought about what you would want to have happen with the things in the house if you and Mom were no longer to live here? What concerns or special wishes would you have?” “What if we had to make decisions about what happens to your belongings, like your quilts and family photographs? What would you want us to do?”

Any of these questions can create anxiety for both the person raising the issues and the person trying to answer. You can provide reassurances by saying something like, “Chances are you will be living here for a long time, but if you would have to move or if you are unable to make those decisions in the future, I would like to know what you want so your wishes can be carried out.”

Look for natural opportunities to initiate a conversation. When a friend or relative is dealing with transferring personal belongings, use the situation to introduce the topic. Or, describe a situation of a friend who recently experienced dividing up his or her property. Follow up the story by asking, “What would you have done if you were in that situation?”

If the other person refuses to talk or denies the possibility of ever having to deal with transferring personal property, you cannot force his or her involvement. You have a right to share your feelings and may feel better because you made the effort.

Determine What You Want to Accomplish

If you are thinking about the distribution of your non-titled property, there are several questions to ask yourself. What is it that you hope to accomplish when your non-titled property is transferred? Have you thought about what’s most important to you?

If you have items, such as a clock or painting that are considered owned by you and your spouse, do you know what is most important to him or her when transferring mutual personal property? Have you taken time to think about, share and discuss your transfer goals with your spouse?

An important part of transferring personal property is identifying your goals and coming to an agreement on what you want to accomplish with other co-owners. Goals need to be identified to determine what you and other co-owners want to happen. Decide what you hope to accomplish with the property transfer process. Is preserving memories of primary importance? How important is maintaining or improving family relationships? Is it important to treat everyone in the family equally, or to recognize differences?

Some individuals prefer to take differences among family members into account with a desire to be equitable when transferring personal belongings. Considerations may include contributions over the years (care, gifts), needs (financial, emotional, physical), and other differences among family members such as age, birth order or marital status. Do you wish to maintain privacy and control within your family? Do you want to contribute to society, such as donating historical items to a museum?

Addressing these types of questions will help determine your goals. The method of property transfer you select should be based on the goals you have identified as an individual, as a couple, or as a family. Once goals are identified it is easier to decide how to best accomplish them.

Another benefit of identifying goals is letting potential receivers know what you are trying to accomplish. This can help avoid misunderstandings and assumptions about your intentions.

Determine What Fair Means in Your Family

Many people say they want to be fair to all members of their family when their belongings are transferred. What does fair mean? Different perceptions about what is fair are inevitable and normal. There can be many different ideas of what would make both the process and end result fair when deciding who gets what personal belongings. What unwritten rules or assumptions do members of your family have about what is fair when transferring non-titled personal property?

Some individuals may feel the process used to decide the way in which transfers are done is more important than who actually gets the items. For example, family members may feel good about the end result if each person’s viewpoint is heard or if a lottery system is used to divide up important items.

Different feelings about who should be involved and when transfers should occur can be the source of disagreements. The issue of who is and is not family can quickly arise. Is it fair if the daughters-in-law are involved and the sons-in-law are not? Is it fair that one son gets to receive items now, while other siblings have to wait? Is it fair that local grandchildren are involved while those that live far away are not?

Does fair always mean equal? No! Some family members consider the distribution of belongings to be fair when everyone has received an equal amount. In this case, differences among family members are not emphasized. When dealing with non-titled property, challenges quickly arise about whether equal means an equal number of items, equal dollar value, or equal in terms of emotional value. What makes dividing equally even more difficult is that the sentimental meaning or value of items will differ for each individual. What one person considers as equal emotional value may not be what another would consider equal. Some personal belongings may or may not have financial value. Who determines the value of an item and whether the value is measured in emotional terms, dollars and cents, or some combination?

Research has shown that disputes over inheritance and property distribution are one of the major reasons for adult siblings to break off relationships with one another. Attorneys who work with estate planning say that often it is the personal property, not the titled property, that causes the most problems when settling an estate. Material possessions seem to become more valuable and bring a greater potential for conflict when the titled property or the rest of the estate is not large in dollar value.

The challenge of how to divide personal property fairly when the value is not easily measured in dollars adds sensitivity to property transfers. Different ideas of what is fair can make the process and the results of property transfer decisions frustrating, hurtful and damaging to relationships. On the other hand, taking time to understand family members’ different perceptions of what is fair can reduce misunderstandings, help them learn about one another’s wishes and strengthen relationships.

Identify the Meaning of Personal Possessions

While Grandma’s yellow pie plate or Dad’s gun collection are material possessions, there may be memories, emotions and feelings triggered by such personal belongings. Recognize that personal property may have sentimental value to both current owners and potential receivers. Also realize that for some, such items may not carry as much meaning and indeed may be considered as just “stuff” or “junk.”

The sentimental value assigned to belongings by someone who is 83 years old may be different from that of someone who is 57 or 23 years old. Grandpa’s journal may seem like just a dust collector to a grandchild who is 7, but may be considered a treasure of family history to the son or daughter who is 47 years of age. A husband and wife may name the same special object, but give different reasons why the item is special. One study revealed that when naming special objects, mothers and daughters tend to be more alike in their answers than fathers and sons.

Recognize Distribution Options and Consequences

Families use a variety of methods to distribute non-titled property. Distribution methods that require planning prior to death include: making a gift, labeling items, making a will, and preparing a list of personal property specifying the intended recipient. Auctions and other types of sales held either within the family or for the general public, or an in- family distribution using some kind of selection, such as a lottery, may occur either before or after the death of the property owner.

These methods are frequently used when a person moves into smaller living quarters (for example, moving from a house to an apartment or long-term care facility), as well as after death. When owners fail to plan for non-titled property prior to their death, distribution methods are more limited.

When decisions are made by property owners prior to death, the person transferring the property can consider the wishes of the recipients and pay attention to special memories shared with the recipients. Doing so may help to eliminate misunderstandings about the owner’s wishes. When decisions are made after a death, they may not accurately reflect the wishes of the owner. Very often more than one person feels they have been promised or are entitled to the same item.

No method is perfect or right for all families. For families to find the best method for their situation, they need to first identify goals and then keep these goals in mind as they select a distribution method. Individuals and other family members involved should discuss, identify and agree upon a method or methods of transfer before beginning the distribution process.

Montana Law

While families may be creative as they seek solutions to any problems that arise, they also need to be aware of Montana statutes governing the transfer of property after death and work within the legal guidelines. If you own property at the time of your death, and have not made a will, Montana intestate succession law dictates how your titled and non- titled property will be distributed.

An explanation of how your property is distributed if you die without a will is available in MSU Extension MontGuide Dying Without a Will in Montana (MT198908HR). An interactive website, Dying Without a Will in Montana, is also available at www.montana.edu/dyingwithoutawill.

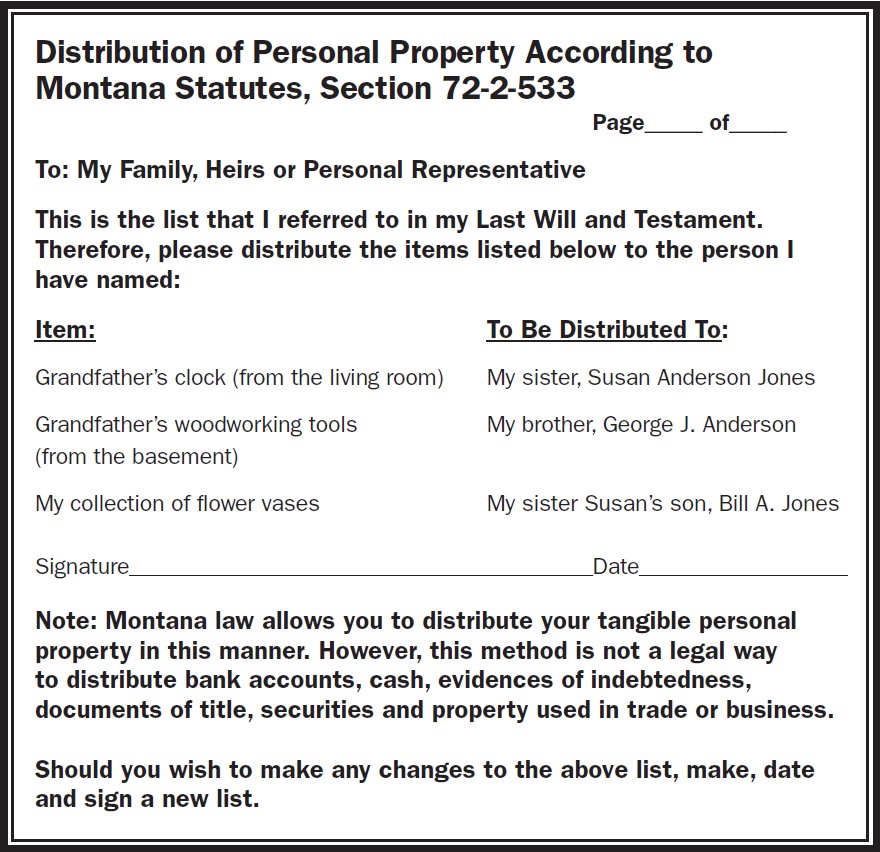

The Montana Uniform Probate Code contains a provision allowing a person to refer in his or her will to a separate listing that disposes of tangible personal property. The list cannot be used to distribute cash, stocks and bonds, mutual funds, other intangible personal property, or real estate. The list is not a part of the will but separate from it. The list must identify both the items and the persons to receive them with reasonable certainty. (For example, “to my niece, Bethany Buczinski, the opal ring that was Grandma Ray’s”.)

The list may be prepared either before or after the will is written. The list can be either in the handwriting of the owner or signed by the owner. The separate listing should be kept with the will so the personal representative is able to distribute items to intended recipients. The separate listing can be changed as new possessions are added without the formalities required for a new will or codicil. The list should be dated and signed each time a change is made (see example below).

Giving Prior to Death

Property may be transferred to others by making a gift of it prior to death. While these gifts frequently take place at birthdays and holidays, they may occur at any time. One grandmother chose to give her grandson’s fiancee a crystal bowl as a shower gift. She included a note explaining that originally the bowl was received as a gift when she and her husband were married 50 years earlier. Gifts of up to $17,000 ($34,000 for married couples), or property equal to that amount, may be gifted annually without paying a federal gift tax. Gifts also allow families to share stories and special memories associated with specific items.

Summary

Transferring personal property can be a time to celebrate a person’s life, share memories and stories, and continue traditions and family history. Sharing stories about special objects helps family members understand their past, discover another aspect of their family and appreciate the real accomplishments of their ancestors. Without consciously asking about family history, a person may have a dim and distorted vision of the past. Sharing stories and meanings about significant belongings helps preserve family history, memories and traditions. There are no magic formulas or solutions available for transferring personal property.

This MontGuide has provided some factors to consider whether you are planning for the transfer of your own personal property or working with family members or personal representatives to plan for the transfer of property of a family member who has died.

Disclaimer

This publication is not intended to be a substitute for legal advice. Rather, it is designed to help families become better acquainted with some of the devices used in estate planning and to create an awareness of the need for such planning. Future changes in laws cannot be predicted, and statements in this MontGuide are based solely upon those laws in force on the date of publication.

Sources

The following resources would be helpful to family members of all generations:

Who Gets Grandma’s Yellow Pie Plate: A Guide to Passing on Personal Belongings Workbook; from the University of Minnesota. Visit extension.umn.edu/later-life-decision-making/who-gets-grandmas-yellow-pie-plate to order a printed Workbook for $12.50 plus shipping.

Who Gets Grandma’s Yellow Pie Plate Video (University of Minnesota-Extension) https://extension.umn.edu/later-life-decision-making/who-gets-grandmas-yellow-pie-plate-video