What’s Wrong with This Tree?

How to prevent and diagnose problems not caused by disease or insects in newly transplanted or long-standing trees.

Last Updated: 12/19by Cheryl Moore-Gough, Extension Horticulturist

DISEASES AND INSECT ATTACKS AREN’T THE ONLY

killers or even major killers of ornamental trees in Montana– physiological stress is the greatest hazard. Here are some guidelines for diagnosis and prevention of physiological problems leading to severe plant stress and death.

Newly Planted or Transplanted

Plant Trees Adapted to the Area

Select tree species adapted to the area. A reputable local nurseryman or the county Extension agent can help choose the right plant. MSU Extension’s Tree & Shrub Selection Guide, EB123, is also a valuable guide for selecting the right landscape plants. Its sister publication, EB162, a Tree & Shrub Grower’s Guide, explains how to properly care for selected plants. See Table 1 on Pages 6–7 for adaptive characteristics of many trees suitable for Montana landscapes.

Consider winter hardiness and other factors such as soil type, pH, and salinity. Salty, alkaline soils in eastern Montana limit the number of species to choose from. Other plants, especially dryland species, suffer from the poor soil drainage and poor aeration found in low lying areas with clay soils. Red- and yellow-twig dogwoods, birch, willows, maples, cottonwoods and mountain ash must be planted in areas with moist soil conditions or be provided with ample supplemental irrigation. High elevation also limits plant selection due to the short growing season and cold winter temperatures.

Planting the wrong tree in the wrong spot is a waste of time and money (Figure 1).

Transplant Shock

Established plants growing under adequate cultural conditions develop a balance between leaf area and root volume. This assures an adequate supply of water and nutrients for sustained growth. Typically, the root system extends well beyond the spread of the branches and a considerable portion of the roots are cut when a tree is moved. Transplanted to a new location, the plant has the same number of leaves to support with a smaller root system to supply water and nutrients, resulting in transplant shock.

Figure 1: Many conditions can cause this all-too-common sight. BY CHERYL MOORE-GOUGH

Symptoms of transplant shock are obvious in trees moved in full leaf or in leaves formed immediately after transplanting. These leaves wilt, and if corrective steps are not taken, may eventually turn brown and drop. Needles of evergreens develop a pale green or blue-green color followed by browning and dropping. Symptoms appear first on the youngest leaves, which are most subject to desiccation.

Sprinkle water on leaves to cool them and reduce water loss from their surfaces. Anti-transpirant sprays such as Wilt Pruf or Wilt Stop are also effective in reducing water loss. Though they reduce water loss, they also temporarily interfere with food production within the leaf. Do not overuse these antidesiccants and always follow label directions.

Figure 2: Misalignment of the root ball with root mass increases the chance of transplant shock.

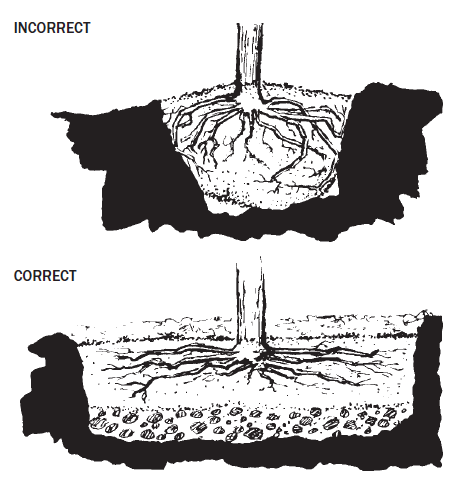

Figure 3: Roots should have ample room to spread in all directions as in the bottom drawing.

Poor Digging and Handling

Improper digging can result in an inadequate root system and greater transplant shock. This is the result of excavating too little soil or misalignment of the root ball with the root mass (Figure 2). In general, allow 12 inches of root ball diameter for every inch of trunk diameter measured 12 inches above the soil line. These guidelines are for nursery-grown plants; increase the size of the root ball for native plants or for those not previously transplanted or root pruned.

Plants dug without soil (bare root) must be transplanted without leaves! Moving trees in full leaf severely stresses the plant. A continuing demand for water when roots have poor contact with the soil causes extra stress. Further, plants grown in containers or dug with a ball of soil (balled and burlapped, or B&B) must be handled with care to avoid dislodging the roots from the soil ball. When handled properly, container grown or B&B trees suffer much less transplant shock than bare-root plants.

Roots of bare root plants must be kept moist until planting, especially those like birch that have fine, fibrous roots. Exposure of roots to the sun and air for as little as one minute can result in up to 50 percent mortality of the fibrous roots. If you must keep bare root plants out of the soil for some time, place them in the shade with the root systems packed in damp sawdust, soil, or other moist media. Ideally, dig and transplant a tree on a cool, cloudy day. Even better, do it in the rain.

Tree roots can be killed by winter temperatures as high as 15°F. Even at higher temperatures, winds can dry the root ball. Never leave plants lying on the soil surface with roots exposed to drying winds and cold temperatures. Even plants in containers can be root-damaged by exposure to cold temperatures or to bright summer sun.

Poor Planting Techniques

Dig the planting hole to a width and depth adequate to avoid cramping the roots. Give them ample room to spread radially in all directions (Figure 3). Ensure good root-soil contact by pulverizing the planting soil. Encourage root growth into the parent soil by minimizing or eliminating the use of soil amendments such as peat moss and compost.

Do not trample the soil around the roots as you backfill the hole. This could break roots and form air pockets. Instead, settle loose soil around the roots with slow-flowing water from a hose. This eliminates air pockets, doesn’t damage roots, and provides complete initial watering. Using B&B or container grown plants reduces backfilling problems at planting time.

After planting, no staking is necessary for trees with limbs close to the ground. Stake bare root and larger B&B trees to keep wind sway from damaging newly formed roots. Use either single or multiple stakes. There are several stake and tie systems available. Ties should be loose enough to allow for slight movement of the tree (Figure 4). This movement strengthens the tree and helps it develop proper taper.

Remove stakes after one year. Trees staked for longer periods become weakened and will not withstand strong winds. Some species of trees transplant more easily than others. See Table 2 on Page 8 for relative ease of transplanting many trees that are adapted to Montana conditions.

Established Trees

Fall Freeze Damage

Plants growing actively in the fall can be damaged by unseasonably early cold periods when temperatures drop into the low 20s or high teens. This type of damage occurs before the plant has become dormant as evidenced by development of fall leaf color and normal leaf drop. The extent of damage ranges from some or all leaves remaining dead on the tree until spring with no twig damage, to death of entire twigs along with the leaves present at time of the freeze. The extent of damage depends upon the duration and depth of the cold spell and upon what stage of growth the tree was in when the cold happened.

Figure 4: Newly planted trees should be staked to prevent wind sway from damaging newly formed roots. BY CHERYL MOORE-GOUGH

Proper fall care of trees usually reduces such damage, except in unseasonably cold seasons. Withholding water and fertilizer in the early fall encourages trees to prepare for winter. However, extreme drought can interfere with a tree’s acclimating for winter. To fill the tree’s water reserves for winter, water only after the leaves have begun to turn color and drop. Continue watering deeply once each week until the soil freezes. Most mature tree and shrub species concentrate their feeder roots in the upper 10 to 12 inches of soil. Therefore, strive to keep this soil volume moist during fall watering.

Tissue at the base of branches, in the branch crotch, and at the base of the tree is last to acclimate to cold. If very low temperatures occur in late fall or early winter these areas may be damaged.

Winter Desiccation

Winter desiccation occurs when winter sun and wind cause excessive water loss from the twigs and leaves, while roots in frozen soil are unable to replace it. The problem is most severe in evergreens, which maintain their large leaf areas during winter. Look for death of twigs and leaves on the windward side or on the side facing the afternoon sun.

Figure 5: Wrap young conifers with burlap to protect from winter’s intense sun and wind. BY CHERYL MOORE-GOUGH

Symptoms may be more severe in recently transplanted plants that have not yet re-established a complete root system.

The best line of defense against winter desiccation is to water all trees and shrubs prior to soil freeze. In addition, winter watering during extended thaw periods when the soil is not frozen is also good practice. Wind and sun barriers are helpful for small and newly transplanted trees. A loose wrapping of burlap works well for young conifers (Figure 5). Never place plastic garbage bags over plants. Air inside these bags can warm to dangerous levels on bright winter days. You can also spray plants in late fall with a film type anti- transpirant to reduce moisture loss from twigs and needles.

Sunscald

Bark on the south and southwest sides of tree trunks and in branch crotches may be killed by sunscald, a particularly prevalent problem in Montana in late winter and early spring (Figure 6). Bark is warmed and the cells de-hardened by afternoon sun. Rapid temperature drop after sunset then kills the cells and bark. Damage is most common on smooth- barked trees such as mountain ash, apple and maple, on trees with dark bark, such as cherry, and on young, thin- barked trees. Shrubs and evergreen trees are rarely affected.

Figure 6: Unprotected young trees may suffer sunscald on the south and southwest side of the trunk. BY CHERYL MOORE-GOUGH

Figure 7: Protect young tree trunks from sunscald and rodents by wrapping with tree wrap or painting with white latex paint. BY CHERYL MOORE-GOUGH

There are several ways to reduce sunscald. Tree wrap, such as that made from heavy kraft paper, can be applied to the trunk in October to reflect the sun and reduce abrupt temperature fluctuations (Figure 7). This also helps keep rodents from feeding on the bark. Remove the wrap in April. White latex paint also reflects the sun and prevents rapid temperature changes. Wrap or paint the trunks from the soil line to the lowest branch. The purpose of tree wraps is not to keep the trunk warm but instead to keep it cool. Evergreen shrubs interplanted with trees help shade the tree bark during winter and reduce sunscald.

Frost Cracking (Vertical Shakes)

Extremely rapid temperature changes in the bark and wood cause tree trunks to split vertically (Figure 8). As with sunscald, the bark and wood on the sunny side of the tree warms during the day. If a cold front moves in with a dramatic temperature drop, say from 30°F to -20°F in a very short time, uneven rapid contraction of the wood causes it to crack.

Damage is most common in hardwood trees such as green ash. Trees usually heal the cracks rapidly. However, once cracked, trees will likely crack again along the same line in similar situations. No practical method is available for preventing shakes, yet they apparently cause no long-term detrimental effects.

Figure 8: Vertical frost cracks are caused by dramatic temperature drops in a short time. BY CHERYL MOORE-GOUGH

Winter Freeze Damage

Plants are subject to branch, twig, and trunk damage during winter thaws when temperatures remain in the 60–70°F range for a week or more. By about Jan. 1 trees have usually satisfied their chilling requirements and can begin to grow when conditions are favorable. Hence, a thaw period mimics springtime conditions. Water flows back into cells, the tissue deacclimates to cold temperatures, and the plant becomes susceptible to freeze damage if temperatures drop rapidly back to seasonal normals. If the change is gradual, even over two to three days, tissue can reacclimate to colder temperatures and damage may not occur. Plants affected by winter freezes can be so damaged that only the main trunk and scaffold branches are viable in the spring. Young trees can be killed to the snow line or the soil line.

Sometimes, patches of bark on limbs and trunks are killed by cold temperatures. The affected area first appears purplish or dark and often somewhat sunken. Eventually, the bark dries, cracks, and can peel from the area. Unlike sunscald, this injury is not limited to the southwest side of the tree.

Tack the bark back into place if it is still alive. Cover the seams with tree wound dressing to reduce desiccation. If the bark is dead, remove it completely and allow the wound to heal. Do not cover this wound with dressing.

Prolonged, severe winter cold when there is no snow cover can kill plant roots. Even acclimated roots can be killed when soil temperatures drop to 10° to 15°F. Snow or mulch protects the tree against this type of damage. Trees with damaged roots usually start growth in spring, but the leaves will be small and both leaves and flowers are likely to wilt shortly after bloom. The tree may die rapidly in summer or may die slowly over a period of years if only a portion of the root system was killed. The tree may recover if the root system was damaged only slightly.

An unusually rampant growth of suckers from the base of the tree is a common symptom of winter freeze damage. The top of the tree may have suffered severe tissue damage, and the suckers are the tree’s way of trying to reestablish a top quickly to balance and maintain the large root system. Attempts to train suckers into becoming a replacement for the original tree are seldom entirely satisfactory.

Spring Frosts

Spring frosts are usually most damaging to flower buds, flowers and young fruit, but can injure tree bark as well. Trees may produce no flowers or fruit but will otherwise look healthy. Often, only a few degrees of warmth for a short period on one or two nights are needed for protection. If you have only one or two young flowering trees, hang a 150 watt infrared heat lamp over them with the rays directed onto the tree. This is most effective on calm nights.

Excess Soil Moisture

Trees develop roots at certain soil depths according to soil oxygen levels. Continuously high soil moisture from poorly drained soils or excessive irrigation can cause “wet feet.” Roots are damaged and the plant’s ability to absorb water and nutrients is reduced. Under these conditions, the tree develops enlarged lenticels on the bark near the trunk base and forms new roots close to the soil surface. Often the deeper, older roots rot away. This makes the tree more subject to wind throw. Removal of the unsightly surface roots can severely damage the growth of the tree.

Montana’s trees are continually stressed by the environment. Even if direct damage does not occur, indirect damage in the form of increased frequency of attacks by insects and diseases can weaken the tree over time. Trees are expensive and valuable—do all you can to keep them healthy.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the original author of this MontGuide, Dr. Bob Gough, former Extension Horticulture Specialist.

Table 1: Adaptive Characteristics

Tolerant of Shade

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Balsam fir | Abies balsamea |

| Alders | Alnus spp. |

| Serviceberry, juneberry | Amelanchier alnifolia |

| Japanese barberry | Berberis thunbergii |

| Red osier dogwood | Cornus sericea |

| Hills-of-snow hydrangea | Hydrangea arborescens var. grandiflora |

| Common juniper | Juniperus communis |

| Honeysuckle | Lonicera spp. |

| Creeping mahonia | Mahonia repens |

| Virginia creeper | Parthenocissus quinquefolia |

| Sweet mock orange | Philadelphus coronaries |

| Potentilla, cinquefoil | Potentilla fruticosa (Pentaphylloides floribunda) |

| Glossy buckthorn | Rhamnus frangula |

| Alpine currant | Ribes alpinum |

| Red elderberry | Sambucus racemosa |

| False spirea | Sorbaria sorbifolia |

| European mountain ash | Sorbus aucuparia |

| Spirea | Spiraea spp. |

| White snowberry | Symphoricarpos albus |

| Yew | Taxus spp. |

| American arborvitae | Thuja occidentalis |

| Hemlock | Tsuga spp. |

| Arrowwood viburnum | Viburnum dentatum |

| European cranberrybush | Viburnum opulus |

| Vinca, periwinkle | Vinca minor |

Drought-tolerant Plants

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Ginnala, Amur maple | Acer ginnala |

| Boxelder, Manitoba maple | Acer negundo |

| Bearberry, kinnikinick | Arctostaphylos uva-ursi |

| Oregon grape | Mahonia aquifolium |

| Japanese barberry | Berberis thunbergii |

| Common pea shrub | Caragana arborescens |

| Pygmy pea shrub | Caragana pygmae |

| Silverberry | Elaeagnus commutata |

| Green ash | Fraxinus pennsylvanica var. lanceolata |

| Common juniper | Juniperus communis |

| Creeping juniper | Juniperus horizontalis |

| Savin juniper | Juniperus sabina |

| Rocky Mountain juniper | Juniperus scopulorum |

| Eastern ninebark | Physocarpos opulifolius |

| Ponderosa pine | Pinus ponderosa |

| Scotch pine | Pinus sylvestris |

| Silver poplar | Populus alba |

| Bolleana white poplar | Populus alba cv. pyramidalis |

| Potentilla, cinquefoil | Potentilla fruticosa (Pentaphylloides floribunda) |

| American plum | Prunus americana |

| Western sandcherry | Prunus besseyi |

| Black cherry | Prunus serotina |

| Glossy buckthorn | Rhamnus frangula |

| Sumac | Rhus spp. |

| Alpine currant | Ribes alpinum |

| Black locust | Robinia pseudoacacia |

| Rugosa rose | Rosa rugosa |

| Buffaloberry | Shepherdia argentea |

| Russet buffaloberry | Shepherdia canadensis |

| Siberian elm | Ulmus pumila |

| Nannyberry viburnum | Viburnum lentago |

Shrubs for Shelterbelts and Windbreaks

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Caragana | Caragana arborescens |

| Red osier dogwood | Cornus sericea |

| Hedge cotoneaster | Cotoneaster lucidus |

| Tatarian honeysuckle | Lonicera tatarica |

| American plum | Prunus americana |

| Western sandcherry | Prunus bessey |

| Nanking cherry | Prunus tomentosa |

| Chokecherry | Prunus virginiana |

| Skunkbush sumac | Rhus trilobata |

| Golden currant | Ribes aureum |

| Blue arctic willow | Salix purpurea |

| Buffaloberry | Shepherdia argentea |

| Common lilac | Syringa vulgaris |

Deciduous Trees for Shelterbelts and Windbreaks

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Hackberry | Celtis occidentalis |

| Green ash | Fraxinus pennsylvanica var. lanceolata |

| Honey locust | Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis |

| Siberian crabapple | Malus baccata |

| Manchurian crabapple | Malus baccata cv. Mandshurica |

| Silver poplar | Populus alba |

| Plains cottonwood | Populus deltoides |

| Robusta poplar | Populus cv. Robusta |

| White willow | Salix alba |

| Golden willow | Salix alba cv. Vitellina |

| Siberian elm | Ulmus pumila |

Evergreens for Shelterbelts and Windbreaks

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Rocky Mountain juniper | Juniperus scopulorum |

| White spruce | Picea glauca |

| Colorado blue spruce | Picea pungens |

| Limber pine | Pinus flexilis |

| Ponderosa pine | Pinus ponderosa |

| Scotch pine | Pinus sylvestris |

| Douglas fir | Pseudotsuga menziesii |

Evergreens for City Conditions

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Pfitzer juniper | Juniperus chinensis var. pfitzeriana |

| Oregon grape | Mahonia aquifolium |

| Colorado blue spruce | Picea pungens |

| Yews | Taxus spp. |

| Periwinkle | Vinca minor |

Deciduous Shrubs for City Conditions

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Amur maple | Acer ginnala |

| Japanese barberry | Berberis thunbergii |

| Pea shrub, caragana | Caragana arborescens |

| Red osier dogwood | Cornus sericea |

| Yellow twig dogwood | Cornus sericea cv. Flaviramea |

| Euonymus | Euonymus spp. |

| Hydrangea | Hydrangea spp. |

| Honeysuckles | Lonicera spp. |

| Potentilla, cinquefoil | Potentilla fruticosa (Pentephyllioides floribunda) |

| Glossy buckthorn | Rhamnus frangula |

| Sumacs | Rhus spp. |

| Alpine currant | Ribes alpinum |

| Rugosa rose | Rosa rugosa |

| Elderberry | Sambucus canadensis |

| False spirea | Sorbaria sorbifolia |

| Bumald spirea | Spiraea x bumaldi |

| Bridal wreath spirea | Spiraea x vanhouttei |

| White snowberry | Symphoricarpos albus |

| Preston lilac | Syringa x prestoniae |

| Common lilac | Syringa vulgaris |

| Arrowwood viburnum | Viburnum dentatum |

| Wayfaring tree viburnum | Viburnum lantana |

| Nannyberry viburnum | Viburnum lentago |

| European cranberrybush | Viburnum opulus |

Deciduous Trees for City Conditions

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Amur maple | Acer ginnala |

| Boxelder | Acer negundo |

| Norway maple | Acer platanoides |

| Horse chestnut | Aesculus hippocastanum |

| Hackberry | Celtis occidentalis |

| English hawthorn | Crataegus laevigata |

| Green ash | Fraxinus pennsylvanica var. lanceolata |

| Honey locust | Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis |

| Apples and crab apples | Malus spp. |

| Silver popular | Populus alba |

| Boleana (white) poplar | Populus alba cv. Pyramidalis |

| Lombardy poplar | Populus nigra cv. Italica |

| Black locust | Robinia pseudoacacia |

| Japanese tree lilac | Syringa reticulata |

| Lindens | Tilia spp. |

| American elm | Ulmus Americana |

| Siberian elm | Ulmus pumila |

Vines for City Conditions

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Bittersweet | Celastrus spp. |

| Honeysuckles | Lonicera spp. |

| Virginia creeper | Parthenocissus quinquefolia |

| Boston ivy | Parthenocissus tricuspidata |

Trees and Shrubs Tolerant of Standing Water

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Balsam fir | Abies balsamea |

| Thin-leaf alder | Alnus incana |

| Water birch | Betula occidentalis |

| Hackberry | Celtis occidentalis |

| Red osier dogwood | Cornus sericea |

| Yellow twig dogwood | Cornus sericea cv. Flaviramea |

| Green ash | Fraxinus pennsylvanica var. lanceolata |

| Willow | Salix spp. |

| American arborvitae | Thuja occidentalis |

| American linden | Tilia americana |

| American elm | Ulmus americana |

| Arrowwood viburnum | Viburnum dentatum |

| European cranberrybush | Viburnum opulus |

| American cranberrybush | Viburnum trilobum |

Table 2: Relative Ease of Transplanting

| Easy | Moderately Difficult | Difficult |

| Alder | Crabapple | Birch |

| American elm | Buckeye | Dogwood |

| American linden | Bur oak | Hawthorn |

| Catalpa | Cherry | Pin cherry |

| Common pear | Hemlock | Pines (most) |

| Eastern red cedar | Horsechestnut | Walnut |

| Fir | Larch | White oak |

| Green ash | Linden | |

| Hackberry | Red maple | |

| Honeylocust | Red oak | |

| Jack pine | Spruce | |

| Locust | Ussurian pear | |

| Mountain ash | ||

| Poplar | ||

| Silver maple | ||

| Sugar maple | ||

| Sumac | ||

| Yew |